Susan reporting:

The Hon. George Dalrymple (d. 1745) was the third son of the first Earl of Stair. His older brother John (1673-1747) was much the more famous*, as an army officer, politician, and diplomat. Such is often the way with heirs to peerages; poor George seems to have been so thoroughly in his older brother's shadow that even his birthdate is now forgotten.

But in January, 1715, John journeyed to France as the newly appointed minister-plenipotentiary at Paris (aka the English ambassador), and George accompanied him. While John had a great many official duties to tend to, younger brother George had plenty of time to check out the female sights. Clearly he could have used the advice of a travel guide such as that would be written later in the century by Captain Thicknesse. George seems to have felt the usual English gentleman's disappointment (and the usual xenophobia) for the French ladies, as this excerpt from one of his letters proves:

"I have not been long enough here, to know, whether London or Paris is the most diverting town. The people here are more gay, the ladies less handsome, and much more painted, love gallantry more than pleasure, and coquetry more than solid love. This place is good for all those that have more vanity than real lust....This is the most diverting time to be at Paris because of the Fair Saint Germain. All the ladies go their every night at six o'clock and stay till ten. All that time they stroll about from the fair to the play and rope dancing and the rest of the things to be seen there and I am sure if the people there have a mind to be happy there is no difficulty to lose themselves. It is impossible to take more freedom, than that place allows of, and men and women stroll about without ceremony and everybody are taken up with their own projects so much that they do not mind what other people are doing. I am sure were such opportunities at London there would be many happy lovers. My brother being here makes it easy for me to get into good company though I am not as yet in love with anybody nor are the ladies handsome. I believe I shall only make love as I used to do to some chambermaid. I have already had some adventures of that kind."

Above: La Foire St. Germain, 1764.

* Another side-note about John Dalrymple: researching the background for this blog, I discovered that he was a F.O.M.C. – Friend of My Characters. In the army, he served as an aide-de-camp to John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough (the duke in Duchess), who became Dalrymple's patron and mentor. And when Dalrymple was eventually promoted to general and compelled to give up his regiment, he sold it to another Scotsman, David Colyear, Earl of Portmore, and the husband of Katherine Sedley, the heroine of The Countess and the King. It's a small world there in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography....

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

The Fashionable Archer in 1831

Loretta reports:

If looking at history teaches us anything, it's to beware of making generalizations. In my blog about Mrs. Bennet's nerves, author Thomas Trotter told us that girls were discouraged from getting exercise. Yet that really isn't the complete picture. Just as today there are extremes of fashionable dress, practiced by a minority, there were extremes of behavior. We know that women rode and drove even in the Victorian era. Bingley's sisters might laugh at Elizabeth for walking to Netherfield, but walking was deemed a healthful exercise, and many upper class women prided themselves on being able to walk long distances.

The following excerpt from an 1831 La Belle Assemblée indicates that many fashionable women knew their way around a bow and arrow.

~~~

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

ON

FASHIONS AND DRESS.

THAT truly English pastime, archery, the delight of our forefathers and foremothers (no cavilling, good reader—we insist upon our right to coin a word now and then), is once more become fashionable ; and we hasten to present our fair readers with two dresses equally elegant and appropriate for that healthful and delightful amusement.

FASHIONS FOR SEPTEMBER, 1831.

EXPLANATION OF THE PRINTS OF THE FASHIONS.

ARCHERY DRESSES.

FIRST ARCHERY DRESS. A DRESS composed of changeable gros de Naples, green shot with white. The corsage, made nearly, but not quite, up to the throat, fastens in front by a row of gold buttons, which are continued at regular distances from the waist to the bottom of the skirt. The corsage sits close to the shape. The upper part of the sleeve forms a double bouffant, but much smaller than is usually worn. This is a matter of necessity, as the fair archer would otherwise cut it in pieces in drawing her bow. The remainder of the sleeve sits close to the arm. The brace, placed upon the right arm, is of primrose kid to correspond with the gloves. The belt fastens with a gold buckle ; on the right side, is a green worsted tassel used to wipe the arrow ; a green watered ribbon sustains the petite poche, which holds the arrows on the left side. A lace collar, of the pelerine shape, falls over the upper part of the bust. White gros des Indes hat, with a round and rather large brim, edged with a green rouleau, and turned up by a gold button and loop. A plume of white ostrich feathers is attached by a knot of green ribbon to the front of the crown. The feathers droop in different directions over the brim. The half-boots are of green reps* silk, tipped with black.

So as not to make a loooong blog, I'm putting the description of the Second Archery Dress at Loretta Chase...In Other Words.

*Reps: A French silk fabric having organzine warp the ribs are either warp or cross ribs. (From Louis Harmuth's Dictionary of Textiles (1915)

If looking at history teaches us anything, it's to beware of making generalizations. In my blog about Mrs. Bennet's nerves, author Thomas Trotter told us that girls were discouraged from getting exercise. Yet that really isn't the complete picture. Just as today there are extremes of fashionable dress, practiced by a minority, there were extremes of behavior. We know that women rode and drove even in the Victorian era. Bingley's sisters might laugh at Elizabeth for walking to Netherfield, but walking was deemed a healthful exercise, and many upper class women prided themselves on being able to walk long distances.

The following excerpt from an 1831 La Belle Assemblée indicates that many fashionable women knew their way around a bow and arrow.

~~~

GENERAL OBSERVATIONS

ON

FASHIONS AND DRESS.

THAT truly English pastime, archery, the delight of our forefathers and foremothers (no cavilling, good reader—we insist upon our right to coin a word now and then), is once more become fashionable ; and we hasten to present our fair readers with two dresses equally elegant and appropriate for that healthful and delightful amusement.

FASHIONS FOR SEPTEMBER, 1831.

EXPLANATION OF THE PRINTS OF THE FASHIONS.

ARCHERY DRESSES.

FIRST ARCHERY DRESS. A DRESS composed of changeable gros de Naples, green shot with white. The corsage, made nearly, but not quite, up to the throat, fastens in front by a row of gold buttons, which are continued at regular distances from the waist to the bottom of the skirt. The corsage sits close to the shape. The upper part of the sleeve forms a double bouffant, but much smaller than is usually worn. This is a matter of necessity, as the fair archer would otherwise cut it in pieces in drawing her bow. The remainder of the sleeve sits close to the arm. The brace, placed upon the right arm, is of primrose kid to correspond with the gloves. The belt fastens with a gold buckle ; on the right side, is a green worsted tassel used to wipe the arrow ; a green watered ribbon sustains the petite poche, which holds the arrows on the left side. A lace collar, of the pelerine shape, falls over the upper part of the bust. White gros des Indes hat, with a round and rather large brim, edged with a green rouleau, and turned up by a gold button and loop. A plume of white ostrich feathers is attached by a knot of green ribbon to the front of the crown. The feathers droop in different directions over the brim. The half-boots are of green reps* silk, tipped with black.

So as not to make a loooong blog, I'm putting the description of the Second Archery Dress at Loretta Chase...In Other Words.

*Reps: A French silk fabric having organzine warp the ribs are either warp or cross ribs. (From Louis Harmuth's Dictionary of Textiles (1915)

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

It's All in the Details: An Amazing Sleeve from 1830

Susan reports:

Loretta has shown us many examples of the exuberant gowns of the 1820s-30s (such as the detail, below, from this blog), and has even revealed exactly how those poufy sleeves were kept, well, so poufy. But often the fashion plates of the time are much like the editorial pages of modern high-fashion magazines, exaggerating to make their stylish point. It can be hard to imagine how real women would actually wish to wear some of these fashions, let alone maneuver through doorways.

Until, that is, a delicious dose of reality appears in an actual gown from the era. Above is a detail of a sleeve and bodice from an English dress, c. 1830. The sleeve is like some sort of wonderful, sculptural wing, and the intricate pleating and folding that gives it its shape is almost like origami. I know we have many seamstresses among our readers; can you imagine what the flat pattern for this sleeve must look like? There's an elegance here that the fashion plates can't begin to capture, and the fortunate lady who wore this blush-pink confection must have made an unforgettable entrance indeed.

This gown is included in the upcoming exhibition, Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail, 1700-1915, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. You lucky folk in LA will be able to check it out from October 2, 2010-March 6, 2011. For the rest of us, here's a gallery of photographs of some of the highlights of the show, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times, and here is the book that accompanies the show.

that accompanies the show.

Above right: Evening Dress, detail of a fashion plate from The Atheneum, or Spirit of the English Magazine, July, 1831.

Loretta has shown us many examples of the exuberant gowns of the 1820s-30s (such as the detail, below, from this blog), and has even revealed exactly how those poufy sleeves were kept, well, so poufy. But often the fashion plates of the time are much like the editorial pages of modern high-fashion magazines, exaggerating to make their stylish point. It can be hard to imagine how real women would actually wish to wear some of these fashions, let alone maneuver through doorways.

Until, that is, a delicious dose of reality appears in an actual gown from the era. Above is a detail of a sleeve and bodice from an English dress, c. 1830. The sleeve is like some sort of wonderful, sculptural wing, and the intricate pleating and folding that gives it its shape is almost like origami. I know we have many seamstresses among our readers; can you imagine what the flat pattern for this sleeve must look like? There's an elegance here that the fashion plates can't begin to capture, and the fortunate lady who wore this blush-pink confection must have made an unforgettable entrance indeed.

This gown is included in the upcoming exhibition, Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail, 1700-1915, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. You lucky folk in LA will be able to check it out from October 2, 2010-March 6, 2011. For the rest of us, here's a gallery of photographs of some of the highlights of the show, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times, and here is the book

Above right: Evening Dress, detail of a fashion plate from The Atheneum, or Spirit of the English Magazine, July, 1831.

Monday, September 27, 2010

Mrs. Bennet's Nerves, causes thereof

Loretta reports:

Curious about Mrs. Bennet’s* delicate nerves, and what exactly that meant in Jane Austen’s time, I found some surprisingly modern viewpoints in this book, published in 1808: A view of the nervous temperament: being a practical inquiry into the increasing prevalence, prevention, and treatment of those diseases commonly called nervous, bilious, stomach & liver complaints, by Thomas Trotter.

~~~

Nature has endued the female constitution with greater delicacy and sensibility than the male, as destined for a different occupation in life. But fashionable manners have shamefully mistaken the purposes of nature; and the modern system of education, for the fair sex, has been to refine on this tenderness of frame, and to induce a debility of body, from the cradle upwards, so as to make feeble woman rather a subject for medical disquisition, than the healthful companion of our cares…That it should be rude for an innocent young girl to run about with her brother, to partake of his sports, and to exercise herself with equal freedom, is a maxim only worthy of some insipid gossip, who has the emolument of the family physician and apothecary solely in view. A man of fortune and wealth, when he builds a stable or a dog-kennel for his horses or hounds, takes care that these companions of his field-sports shall be duly preserved sound in wind and limb, by frequent exercise out of doors, when he does not hunt.— But in no part of his premises do you see a gymnasium for his children…But we indulge our boys to yoke their go-carts, and to ride on long rods, while little miss must have her more delicate limbs trampt by sitting the whole day dressing a doll. Ancient custom has been pleaded in favour of these amusements for boys, as we read in Horace : but it is no where recorded, that the infancy of Portia, Arria, and Agrippina was spent in fitting clothes for a joint-baby…

Curious about Mrs. Bennet’s* delicate nerves, and what exactly that meant in Jane Austen’s time, I found some surprisingly modern viewpoints in this book, published in 1808: A view of the nervous temperament: being a practical inquiry into the increasing prevalence, prevention, and treatment of those diseases commonly called nervous, bilious, stomach & liver complaints, by Thomas Trotter.

~~~

Nature has endued the female constitution with greater delicacy and sensibility than the male, as destined for a different occupation in life. But fashionable manners have shamefully mistaken the purposes of nature; and the modern system of education, for the fair sex, has been to refine on this tenderness of frame, and to induce a debility of body, from the cradle upwards, so as to make feeble woman rather a subject for medical disquisition, than the healthful companion of our cares…That it should be rude for an innocent young girl to run about with her brother, to partake of his sports, and to exercise herself with equal freedom, is a maxim only worthy of some insipid gossip, who has the emolument of the family physician and apothecary solely in view. A man of fortune and wealth, when he builds a stable or a dog-kennel for his horses or hounds, takes care that these companions of his field-sports shall be duly preserved sound in wind and limb, by frequent exercise out of doors, when he does not hunt.— But in no part of his premises do you see a gymnasium for his children…But we indulge our boys to yoke their go-carts, and to ride on long rods, while little miss must have her more delicate limbs trampt by sitting the whole day dressing a doll. Ancient custom has been pleaded in favour of these amusements for boys, as we read in Horace : but it is no where recorded, that the infancy of Portia, Arria, and Agrippina was spent in fitting clothes for a joint-baby…

Sunday, September 26, 2010

Avoiding the Sun with Lola Montez in 1858

Susan reporting:

Beauty advice from the past is often amusing to modern readers. The various concoctions that ladies in earlier eras used to "improve" the complexions range from charmingly benign (dew collected before dawn from the petals of roses) to unpleasantly bizarre (puppy urine) to appallingly lethal (white lead.) But every so often, there's advice that seems as if it could appear in any current fashion magazine for 21st c. beauties.

This excerpt comes from The Arts of Beauty; or Secrets of a Lady's Toilet, written in 1858 by the legendary actress, dancer, and courtesan Lola Montez (1820-1861). Lola's life is so colorful that she deserves to become an Intrepid Lady; what better way to describe an Irish girl born as Eliza Gilbert who creatively transformed herself into the exotic Lola Montez, Spanish dancer, lover of composer Franz Listz, and mistress to Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria (he made her Countess of Landesfeld), and whose journeys took her from the royal courts of Europe to Gold Rush San Francisco, and ever to the equally untamed wilds of Australia?

Today, however, we're offering only Lola's advice on "Habits that Destroy the Complexion." Substitute sun block for every mention of a bonnet and veil, and her cautions would please even the strictest modern dermatologist.

"There are many disorders of the skin which are induced by culpable ignorance, and which owe their origin entirely to circumstances connected with fashion or habit. The frequent and sudden changes in this country [she was writing in New York City] from heat to cold, by abruptly exciting or repressing the secretions of the skin, roughen its texture, injure its hue, and often deform it with unseemly eruptions....The habit ladies have of going into the open air without a bonnet, and often without a veil, is a ruinous one for the skin. Indeed, the present fashion of the ladies' bonnets, which only cover a few inches of the back of the head, is a great tax upon the beauty of the complexion. In this climate, especially, the head and face need protection from the atmosphere. Not only a woman's beauty, but her health requires that she should never step in the open air without a sufficient covering to her head. And, if she regards the beauty of her complexion, she must never go out into the hot sun without her veil...If she will not attend to these rules, she will be fortunate, saying nothing about her beauty, if her life does not pay the penalty of her thoughtlessness."

Above: Lola Montez, by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1847

Beauty advice from the past is often amusing to modern readers. The various concoctions that ladies in earlier eras used to "improve" the complexions range from charmingly benign (dew collected before dawn from the petals of roses) to unpleasantly bizarre (puppy urine) to appallingly lethal (white lead.) But every so often, there's advice that seems as if it could appear in any current fashion magazine for 21st c. beauties.

This excerpt comes from The Arts of Beauty; or Secrets of a Lady's Toilet, written in 1858 by the legendary actress, dancer, and courtesan Lola Montez (1820-1861). Lola's life is so colorful that she deserves to become an Intrepid Lady; what better way to describe an Irish girl born as Eliza Gilbert who creatively transformed herself into the exotic Lola Montez, Spanish dancer, lover of composer Franz Listz, and mistress to Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria (he made her Countess of Landesfeld), and whose journeys took her from the royal courts of Europe to Gold Rush San Francisco, and ever to the equally untamed wilds of Australia?

Today, however, we're offering only Lola's advice on "Habits that Destroy the Complexion." Substitute sun block for every mention of a bonnet and veil, and her cautions would please even the strictest modern dermatologist.

"There are many disorders of the skin which are induced by culpable ignorance, and which owe their origin entirely to circumstances connected with fashion or habit. The frequent and sudden changes in this country [she was writing in New York City] from heat to cold, by abruptly exciting or repressing the secretions of the skin, roughen its texture, injure its hue, and often deform it with unseemly eruptions....The habit ladies have of going into the open air without a bonnet, and often without a veil, is a ruinous one for the skin. Indeed, the present fashion of the ladies' bonnets, which only cover a few inches of the back of the head, is a great tax upon the beauty of the complexion. In this climate, especially, the head and face need protection from the atmosphere. Not only a woman's beauty, but her health requires that she should never step in the open air without a sufficient covering to her head. And, if she regards the beauty of her complexion, she must never go out into the hot sun without her veil...If she will not attend to these rules, she will be fortunate, saying nothing about her beauty, if her life does not pay the penalty of her thoughtlessness."

Above: Lola Montez, by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1847

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Imagining Social Networking Media in 1667 (Silly Historical Video)

This one is very short but sweet, and features both the subject of Johannes Vermeer's Girl with a Pearl Earring and our favorite Restoration diarist Samuel Pepys. Produced by a firm of British attorneys who specialize in protecting intellectual property, this quick film is one of a series highlighting the "potential of your imagination to change our world." That's a grand goal, but we liked this video because it made us laugh. Be sure to pause to read the other Tweets that Sam is receiving from other 17th century friends like John Evelyn.

Here's a background blog about making the film, including the costuming and casting: clearly fellow history-nerds at work!

Thursday, September 23, 2010

Hare Townsend, ladies' man of the early 19th C

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:From The Rambler's magazine: or, Fashionable emporium of polite literature, Volume 2, 1823

ANECDOTES OF HARE T—N—D—MR.HARE T—N—D the M.P. is celebrated for his gallantry, and there are many anecdotes related of his amours, which shew him to be a very singular lover, and always a liberal one.

At a meeting of governors, to consider the funds of the Liverpool Lying-in Hospital, Mr. Hare sent a donation of £50; upon which, a governor remarked : " This is very liberal, for, if I mistake not, Mr. Hare is an annual subscriber." That I do not know, said the attendant accoucheur,* but I am certain he is an annual supplyer, and furnishes us with more practice than all the room besides.

A cockney who had long wished for a family, and had a wife more inclined to breed mischief than any thing else, removed her into Lancashire, not many miles from W—l—n, the seat of Mr. Hare T—n—d. There, to his great joy, she conceived and brought forth twins. The Reverend and witty Jack Pigot was in company with the citizen, when a friend remarked how extraordinary it was that the lady should bear children when she had been ten years married, without ever giving signs if such a happy event before. I think, said the husband, it is all owing to this country air.—No doubt, replied Jack Pigot, we are blessed with a fine Hare in this country that makes every woman breed like a rabbit. ——

…

Meeting once a little ragged urchin begging, he stopt to relieve him, and remarked: You are a fine boy, where is your mother — In the workhouse, please your worship. And who was your father, my little fellow !—I never had a father, said the child. Ah! muttered T—n—d as he walked away: 'Tis the first time I ever knew a child to be fatherless, and me in the parish.

A man and a woman were brought before him and some other magistrates. The woman was very great with child, and the bench suggested the man's commitment to gaol. Let me question them first, said Mr. Hare T—n—d. A pretty pair you are, said he, to get children without being married, how comes this ? Please your worship, replied the trembling sinners: We could'nt help it. Ah! observed he, and it were a sin to punish people for what they can't help; and as for once I did not help to get this child, I'll help you to get through the world with it. I have a fellow-feeling for you, as God knows I myself am often condemned for what I could not help.

A man and a woman were brought before him and some other magistrates. The woman was very great with child, and the bench suggested the man's commitment to gaol. Let me question them first, said Mr. Hare T—n—d. A pretty pair you are, said he, to get children without being married, how comes this ? Please your worship, replied the trembling sinners: We could'nt help it. Ah! observed he, and it were a sin to punish people for what they can't help; and as for once I did not help to get this child, I'll help you to get through the world with it. I have a fellow-feeling for you, as God knows I myself am often condemned for what I could not help.*obstetrician

Wednesday, September 22, 2010

The Crooked Town of Boston

Susan reports:

As anyone who has walked along the tables of a flea market knows, there seems to be a basic human need to commemorate people and events on pottery. Recent presidents (and presidential hopefuls), World Series champions, and even Big Bird can be found on mugs, plates, and ashtrays.

Museums, too, have shelf after shelf of creamware commemorating long-past shipwrecks, battles, and even more presidents – plus kings and queens. But just when we think we've seen it all (the cast of Twilight on a pet food bowl, anyone?), we come across an example that is just plain bewildering, even to a Nerdy History Girl. Especially to a Nerdy History Girl.

The legend on this English-made jug: "SUCCESS to the Crooked but interesting Town of BOSTON!" Were the politicians of Boston already so infamous – albeit interesting – by 1800 that they merited an import jug of their own? And why wish them success in their crookedness?

Alas, the explanation is much less intriguing. Once the American Revolution had ended, British manufacturers were perfectly happy to put ill-will behind them for the sake of pleasing the new nation of potential consumers across the ocean. Potters were quick to produce creamware featuring American heroes like George Washington for export. Boston, that former hotbed of rebellion, was now praised and glazed as the new home of liberty. But long before the days of Sam Adams, Boston had also been famous for its narrow, winding streets, and dubbed a "crooked town" because of them. Thus the maker of this jug intended to praise the quaintness of Boston, not comment on the Bostonians' honesty – but it's probably no accident that this particular jug was not a popular model, and is today rare.

Above: Jug, probably Staffordshire, England, 1808-15, Winterthur Museum, Gift of S. Robert Teitelman

As anyone who has walked along the tables of a flea market knows, there seems to be a basic human need to commemorate people and events on pottery. Recent presidents (and presidential hopefuls), World Series champions, and even Big Bird can be found on mugs, plates, and ashtrays.

Museums, too, have shelf after shelf of creamware commemorating long-past shipwrecks, battles, and even more presidents – plus kings and queens. But just when we think we've seen it all (the cast of Twilight on a pet food bowl, anyone?), we come across an example that is just plain bewildering, even to a Nerdy History Girl. Especially to a Nerdy History Girl.

The legend on this English-made jug: "SUCCESS to the Crooked but interesting Town of BOSTON!" Were the politicians of Boston already so infamous – albeit interesting – by 1800 that they merited an import jug of their own? And why wish them success in their crookedness?

Alas, the explanation is much less intriguing. Once the American Revolution had ended, British manufacturers were perfectly happy to put ill-will behind them for the sake of pleasing the new nation of potential consumers across the ocean. Potters were quick to produce creamware featuring American heroes like George Washington for export. Boston, that former hotbed of rebellion, was now praised and glazed as the new home of liberty. But long before the days of Sam Adams, Boston had also been famous for its narrow, winding streets, and dubbed a "crooked town" because of them. Thus the maker of this jug intended to praise the quaintness of Boston, not comment on the Bostonians' honesty – but it's probably no accident that this particular jug was not a popular model, and is today rare.

Above: Jug, probably Staffordshire, England, 1808-15, Winterthur Museum, Gift of S. Robert Teitelman

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Intrepid Women: Sarah Belzoni

Loretta reports:

Here’s a glimpse of what Sarah Belzoni dealt with in Egypt, traveling with her explorer husband (and sometimes on her own) in the early 1800s. The excerpt is from Mrs. Belzoni’s Account of the Women of Egypt, Nubia, and Syria, which was appended to Belzoni’s Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries within the pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (originally published in England in 1820).

~~~

After waiting two months in Cairo, and understanding it might be some time before Mr. B. could return, I determined on a third voyage to Thebes, taking the Mameluke before mentioned. I went to Boolak, and engaged a canja with two small cabins; one held my luggage, and the other my mattress, for which I paid 125 piastres. I left Cairo on November 27th, and arrived at Ackmeim on the 11th December, at night. A heavy rain, accompanied with thunder and lightning, commenced an hour after sunset, and continued the whole of the night: it pourred in torrents. My mattress and coverings were wet through, and were so for some days; and though the rain had ceased, yet it came pouring from the mountains through the lands into the Nile on each side for several days after.

I arrived at Luxor on the 16th, and was informed Mr. B. was gone to the Isle of Philœ: I crossed the Nile, and took up my residence at Beban el Malook. The men left to guard the tomb in Mr. B.'s absence informed me of the heavy rain they had experienced on the night I mentioned, and, in spite of all their efforts, they could not prevent the water entering the tomb; it had carried in a great deal of mud, and, on account of the great heat, and the steam arising from the damp, made some of the walls crack, and some pieces had fallen. On hearing this I went into the tomb, and the only thing we could do was to order a number of boys to take the damp earth away, for while any damp remained the walls would still go on cracking. Mr. B. arrived two days before Christmas, and on St. Stephen's day he crossed to Carnak to review the various spots of earth he had to excavate, when an attempt was made to assassinate him. I had then a violent bilious fever, which, added to this fright, flung me into the yellow jaundice. Having sent a man to procure me some medicine from a doctor at Ackmeim, he returned after five days with about half an ounce of cream of tartar, and two teaspoonsful of rhubarb. Fortunately for me, two English gentlemen happened to arrive, on their return from Nubia for Cairo, and gave me some calomel, which was of great service to me, and which I remember with much gratitude.

hearing this I went into the tomb, and the only thing we could do was to order a number of boys to take the damp earth away, for while any damp remained the walls would still go on cracking. Mr. B. arrived two days before Christmas, and on St. Stephen's day he crossed to Carnak to review the various spots of earth he had to excavate, when an attempt was made to assassinate him. I had then a violent bilious fever, which, added to this fright, flung me into the yellow jaundice. Having sent a man to procure me some medicine from a doctor at Ackmeim, he returned after five days with about half an ounce of cream of tartar, and two teaspoonsful of rhubarb. Fortunately for me, two English gentlemen happened to arrive, on their return from Nubia for Cairo, and gave me some calomel, which was of great service to me, and which I remember with much gratitude.

~~~

Above left: Vue general de Louqsor.

Below right: Karnak. Temple de Ramessés IV, deux Pylônes.

Both by Maison Bonfils (Beirut, Lebanon), photographer, and courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Here’s a glimpse of what Sarah Belzoni dealt with in Egypt, traveling with her explorer husband (and sometimes on her own) in the early 1800s. The excerpt is from Mrs. Belzoni’s Account of the Women of Egypt, Nubia, and Syria, which was appended to Belzoni’s Narrative of the operations and recent discoveries within the pyramids, temples, tombs, and excavations, in Egypt and Nubia (originally published in England in 1820).

~~~

After waiting two months in Cairo, and understanding it might be some time before Mr. B. could return, I determined on a third voyage to Thebes, taking the Mameluke before mentioned. I went to Boolak, and engaged a canja with two small cabins; one held my luggage, and the other my mattress, for which I paid 125 piastres. I left Cairo on November 27th, and arrived at Ackmeim on the 11th December, at night. A heavy rain, accompanied with thunder and lightning, commenced an hour after sunset, and continued the whole of the night: it pourred in torrents. My mattress and coverings were wet through, and were so for some days; and though the rain had ceased, yet it came pouring from the mountains through the lands into the Nile on each side for several days after.

I arrived at Luxor on the 16th, and was informed Mr. B. was gone to the Isle of Philœ: I crossed the Nile, and took up my residence at Beban el Malook. The men left to guard the tomb in Mr. B.'s absence informed me of the heavy rain they had experienced on the night I mentioned, and, in spite of all their efforts, they could not prevent the water entering the tomb; it had carried in a great deal of mud, and, on account of the great heat, and the steam arising from the damp, made some of the walls crack, and some pieces had fallen. On

hearing this I went into the tomb, and the only thing we could do was to order a number of boys to take the damp earth away, for while any damp remained the walls would still go on cracking. Mr. B. arrived two days before Christmas, and on St. Stephen's day he crossed to Carnak to review the various spots of earth he had to excavate, when an attempt was made to assassinate him. I had then a violent bilious fever, which, added to this fright, flung me into the yellow jaundice. Having sent a man to procure me some medicine from a doctor at Ackmeim, he returned after five days with about half an ounce of cream of tartar, and two teaspoonsful of rhubarb. Fortunately for me, two English gentlemen happened to arrive, on their return from Nubia for Cairo, and gave me some calomel, which was of great service to me, and which I remember with much gratitude.

hearing this I went into the tomb, and the only thing we could do was to order a number of boys to take the damp earth away, for while any damp remained the walls would still go on cracking. Mr. B. arrived two days before Christmas, and on St. Stephen's day he crossed to Carnak to review the various spots of earth he had to excavate, when an attempt was made to assassinate him. I had then a violent bilious fever, which, added to this fright, flung me into the yellow jaundice. Having sent a man to procure me some medicine from a doctor at Ackmeim, he returned after five days with about half an ounce of cream of tartar, and two teaspoonsful of rhubarb. Fortunately for me, two English gentlemen happened to arrive, on their return from Nubia for Cairo, and gave me some calomel, which was of great service to me, and which I remember with much gratitude.~~~

Above left: Vue general de Louqsor.

Below right: Karnak. Temple de Ramessés IV, deux Pylônes.

Both by Maison Bonfils (Beirut, Lebanon), photographer, and courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Monday, September 20, 2010

How to Breed a Spoiled Young Gentleman: 1678

Susan reporting:

No matter what the century, there always seems to be a market for books of child-rearing advice. The author of one such 17th c. book, J. Galliard, offered his credentials in the forward as a "gentleman, who hath been a Tutor Abroad to several of the Nobility and Gentry." The lengthy title of his book – The Compleat Gentleman; or, Directions for the Education of Youth as to their Breeding at Home and Travelling Abroad, in Two Treatises – promised exact directions on how to raise a perfect little gentlemen. This book was published in London in 1678, in the merry old days of Charles II and his Restoration court, and considering all the hard-living, hard-drinking libertine mischief that his courtiers were enjoying, worried parents were probably eager for a bit of common sense regarding their own unformed scions.

While Mr. Galliard's advice is more than three hundred years old and the language a bit convoluted, his words remain apt – both for the child, and the parents who spoil him in the name of "fondness."

"I do not deny how decent it is that Children of men of quality should be brought up in a handsomer way than those of common people: but I speak against the fondness which some have for them, which is so far from deserving to be called care, that I more properly name it want of care.

Let the inconveniences of this manner of Breeding be observed. These young Gentlemen. when they come somewhat to know themselves, will eat no coarse meat, but only the most delicate they can find for money. They scorn to wear cloathes except that they be very rich; they will think it is below them to walk, but if they go out, it must be in a Coach;...and if there be no servant to give them a glass of Wine, they will rather be choked than take it themselves. Sometimes the weather is not good for them to walk out, therefore they will sit at home, and Dice or Card away many a pound, or in a Tavern, and drink away their health till the Gout, or Gravel comes upon them, or a Pleurisie, an Apoplexy, or some other sudden Disease carries them to their Grave....What manner of men...who for years were kept as soft and warm as if they had been in their Mothers womb; who would not so much as suffer workmen in the Town for fear their sleep would have been interrupted with the noise made...who made in bed most of their Exercises, and their most serious Discourses at Table, and...look for excesses in every thing. Now I would fain know: what good can be expected from such a Breeding?"

Above: The Children of Charles I of England by Anthony Van Dyck, 1637

No matter what the century, there always seems to be a market for books of child-rearing advice. The author of one such 17th c. book, J. Galliard, offered his credentials in the forward as a "gentleman, who hath been a Tutor Abroad to several of the Nobility and Gentry." The lengthy title of his book – The Compleat Gentleman; or, Directions for the Education of Youth as to their Breeding at Home and Travelling Abroad, in Two Treatises – promised exact directions on how to raise a perfect little gentlemen. This book was published in London in 1678, in the merry old days of Charles II and his Restoration court, and considering all the hard-living, hard-drinking libertine mischief that his courtiers were enjoying, worried parents were probably eager for a bit of common sense regarding their own unformed scions.

While Mr. Galliard's advice is more than three hundred years old and the language a bit convoluted, his words remain apt – both for the child, and the parents who spoil him in the name of "fondness."

"I do not deny how decent it is that Children of men of quality should be brought up in a handsomer way than those of common people: but I speak against the fondness which some have for them, which is so far from deserving to be called care, that I more properly name it want of care.

Let the inconveniences of this manner of Breeding be observed. These young Gentlemen. when they come somewhat to know themselves, will eat no coarse meat, but only the most delicate they can find for money. They scorn to wear cloathes except that they be very rich; they will think it is below them to walk, but if they go out, it must be in a Coach;...and if there be no servant to give them a glass of Wine, they will rather be choked than take it themselves. Sometimes the weather is not good for them to walk out, therefore they will sit at home, and Dice or Card away many a pound, or in a Tavern, and drink away their health till the Gout, or Gravel comes upon them, or a Pleurisie, an Apoplexy, or some other sudden Disease carries them to their Grave....What manner of men...who for years were kept as soft and warm as if they had been in their Mothers womb; who would not so much as suffer workmen in the Town for fear their sleep would have been interrupted with the noise made...who made in bed most of their Exercises, and their most serious Discourses at Table, and...look for excesses in every thing. Now I would fain know: what good can be expected from such a Breeding?"

Above: The Children of Charles I of England by Anthony Van Dyck, 1637

Update: More Ladies with Fans

Susan reporting:

Following up on the recent post featuring House of Duvelleroy fans: quite by coincidence, one of my favorite blogs, It's About Time, just featured two days' worth of beautifully romantic paintings of ladies with fans. If these don't make the case for the return of fans as a graceful accessory, I don't know what will!

First up are ladies with Japanoisme fans by various 19th and 20th c. painters. And if you enjoyed seeing Madame X with her fan, there are a dozen more portraits by John Singer Sargent.

Please check them out, and enjoy.

Above: Mrs. Cecil Wade, by John Singer Sargent

Following up on the recent post featuring House of Duvelleroy fans: quite by coincidence, one of my favorite blogs, It's About Time, just featured two days' worth of beautifully romantic paintings of ladies with fans. If these don't make the case for the return of fans as a graceful accessory, I don't know what will!

First up are ladies with Japanoisme fans by various 19th and 20th c. painters. And if you enjoyed seeing Madame X with her fan, there are a dozen more portraits by John Singer Sargent.

Please check them out, and enjoy.

Above: Mrs. Cecil Wade, by John Singer Sargent

Sunday, September 19, 2010

Fashions for September 1818

Loretta reports,

From La Belle assemblée, Volume 18. Publisher J. Bell, 1818

FASHIONS FOR SEPTEMBER, 1818.

EXPLANATION OF THE PRINTS OF FASHION.

FRENCH. No. 1.—PARISIAN WALKING DRESS.

Round dress of printed muslin, of a cerulean blue spotted with black, with bordered flounces of the same material to correspond : between each flounce a layer placed of black brocaded satin ribband.— Bonnet of straw-coloured gossamer satin, ornamented on the left side with a single full-blown rose, and a plume of white feathers. Cachemire sautoir*, and parasol of barbel blue, fringed with white. Slippers of pale blue kid, and washing leather gloves.

ENGLISH. No. 2.—DINNER DRESS

Round dress of fine Bengal muslin, with a superbly embroidered border; the border surmounted by two flounces richly embroidered at the edges, and headed by muslin bouilloné** run through with Clarence blue satin : Meinengen corsage of the same colour, with small pelerine cape, elegantly finished with narrow rouleaux of white satin and fine lace. Parisian cornette of blond, with a very full and spreading branch of full-blown roses placed in front.

*SAUTOIR, s. m. saltier. (Ne s'emploie que dans la locution adverbiale.)En sautoir, in the form of a cross of Saint Andrew ; cross-wise. Deux épées étaient placées en sautoir sur le cercueil, two swords were placed crosswise on the coffin. Porter un ordre en sautoir, to wear the riband of an order hanging in a point on the breast. Porter quelque chose en sautoir, to wear something slung across the shoulders.

From The royal phraseological English-French, French-English dictionary, Volume 2, by John Charles Tarver (1879).

** Bouilloné.—Puffed ; 1800 and after.

From Historic dress in America, 1800-1870, by Elisabeth McClellan (1910).

From La Belle assemblée, Volume 18. Publisher J. Bell, 1818

FASHIONS FOR SEPTEMBER, 1818.

EXPLANATION OF THE PRINTS OF FASHION.

FRENCH. No. 1.—PARISIAN WALKING DRESS.

Round dress of printed muslin, of a cerulean blue spotted with black, with bordered flounces of the same material to correspond : between each flounce a layer placed of black brocaded satin ribband.— Bonnet of straw-coloured gossamer satin, ornamented on the left side with a single full-blown rose, and a plume of white feathers. Cachemire sautoir*, and parasol of barbel blue, fringed with white. Slippers of pale blue kid, and washing leather gloves.

ENGLISH. No. 2.—DINNER DRESS

Round dress of fine Bengal muslin, with a superbly embroidered border; the border surmounted by two flounces richly embroidered at the edges, and headed by muslin bouilloné** run through with Clarence blue satin : Meinengen corsage of the same colour, with small pelerine cape, elegantly finished with narrow rouleaux of white satin and fine lace. Parisian cornette of blond, with a very full and spreading branch of full-blown roses placed in front.

*SAUTOIR, s. m. saltier. (Ne s'emploie que dans la locution adverbiale.)En sautoir, in the form of a cross of Saint Andrew ; cross-wise. Deux épées étaient placées en sautoir sur le cercueil, two swords were placed crosswise on the coffin. Porter un ordre en sautoir, to wear the riband of an order hanging in a point on the breast. Porter quelque chose en sautoir, to wear something slung across the shoulders.

From The royal phraseological English-French, French-English dictionary, Volume 2, by John Charles Tarver (1879).

** Bouilloné.—Puffed ; 1800 and after.

From Historic dress in America, 1800-1870, by Elisabeth McClellan (1910).

Saturday, September 18, 2010

Silly Historical Video AND an Intrepid Woman: It's Boudicca!

Susan reports:

Enough of fou-fou fans and sleeve puffs. Time for a really, really Intrepid Woman: the legendary Celtic warrior queen Boudicca.

But be forewarned: because this is the weekend, and we Nerdy History Girls tend to go L-I-T-E on the weekend, this is the Horrible Histories version of Boudicca's story. (You remember the Historical Histories telling of King George IV's Solo Career? Or Charles II: King of Bling?) We're sure we needn't say more.

Except all hail, Boudicca, Supah-Stah!

Thursday, September 16, 2010

The Return of the Fashionable Fan?

Susan reporting:

There was a time when no lady would have been without a folding fan. A fan was a utilitarian accessory in an over-heated drawing room, as well as a useful weapon in the arsenal of flirtation. Fans could also be an extraordinary symbol of wealth and taste: a delicately hand-made status symbol par excellence.

Ladies throughout Europe recognized and desired the work of the most skilled fan making houses in Paris, and among the greatest was the House of Duvelleroy, founded in 1827 by Jean-Pierre Duvelleroy. Though the French Revolution had made fans with their aristocratic associations unfashionable, Duvelleroy gambled that the style pendulum would swing back. He gathered the best craftsmen – including workers in ivory, tortoise shell, exotic wood, and horn as well as engravers and painters and other artists skilled in mother-of-pearl inlay, enamel, and even feathers – and created beautiful fans to tempt a generation of ladies who had never known the opulence of the previous century. His gamble paid off. Soon every fashionable lady throughout Europe and America craved a Duvelleroy fan, and he was appointed the fan maker to many of the royal courts. The business continued to grow throughout the 19th century, remaining in the family until the 1940s.

Noted the style-conscious Art Journal in 1851: "No lady's corbeille de mariage [wedding gifts] is considered complete without one of Mr. Duvelleroy's fans. Some of them are indeed perfect bijoux, and are decorated with a profusion of expensive ornament which render them objects of the greatest luxury. Besides being studded with precious stones, the most eminent artists of Paris do not scruple to make their most finished designs upon them."

The fan above is a beautiful example from the 1880s, depicting a pair of romantic 18th c. lovers. The painting is believed to have been done by Alice Helen Loch, an award-winning water colorist. The scene is hand-painted on doubled silk leaves, and embellished with polished brass and steel sequins. The sticks are made from ivory, pierced and decorated with gilt silver and silver pique work, and the rivet is a button of carved mother-of-pearl.

Such exquisite design would seem to have no place in a modern world where it's an iPhone or Blackberry that nestles in a stylish female hand. But as Duvelleroy himself knew, the only thing certain about fashion is that it's always changing. Two young Parisian women have recently purchased what survived of the House of Duvelleroy (sadly reduced by the 21st c. to a service for restoring antique fans), and are determined to bring back the Duvelleroy fan as a must-have accessory. Here's a recent story about their plans, along with a sampling of their gorgeously contemporary designs. Are you tempted?

Above: Pastoral Reprise fan, Duvelleroy, Paris, 1880s. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Below: Photograph of the London showroom of the House of Duvellleroy, c. 1900.

Wednesday, September 15, 2010

Intrepid Women: Helen Rowland

Loretta reports:

~~~

A PERFECT husband, who can find one?

For his price is far above gold bonds.

The grouch knoweth him not and his breakfast always pleaseth him. His mouth is filled with praises for his wife's cooking. He doth not expect chicken salad from left-over veal, neither the making of lobster patties from an ham-bone.

His wife is known within the gates, when she sitteth among the officers of her Club, by the fit of her gowns and her imported hats. He luncheth meagrely upon a sandwich that he may adorn her with fine jewels. He grumbleth not at the bills.

…

BEHOLD, my Daughter, the Lord maketh a man—but the wife maketh an husband.

For Man is but the raw material whereon a woman putteth the finishing touches.

Yea, and whatsoever pattern of husband thou selectest, thou shalt find him like unto a shop-made garment, which must be trimmed over and cut down, and ironed out, and built up to fit the matrimonial situation.

Verily, the best of husbands hath many raw edges, and many unnecessary pleats in his temper, and many wrinkles in his disposition, which must be removed.

~~~

This is a tiny sampling from The Sayings of Mrs. Solomon: Being the Confessions of the Seven Hundredth Wife as Revealed to Helen Rowland (1876-1950). Published in 1913, it’s online at Google Books or you can buy it at Amazon.

I discovered Helen Rowland in the newspaper (fittingly, since she was a journalist) via a Quote for the Day amusing enough to make me to look her up. Online one finds precious little. In addition to the very stubby stub in Wikipedia, there’s a brief (early) bio in a 1914 Woman's Who's Who of America. A 1928 New York Evening Journal booklet described her thusly:

HELEN ROWLAND, Author “Meditations of a Wife” Often referred to as America’s “Bernard Shaw,” and as America’s wittiest woman. Satire sparkles through her writings. Her observations on the foibles of men and women, the joys and sorrows of love and marriage, and the relief or the lack of it in divorce are always brilliant and entertaining, yet always “said with a smile.” Helen, like George Cohan, says: “I always leave ’em laughing when I say good-bye.”

Maybe the best way to get to know the eminently quotable Ms. Rowland is to read her—online at Project Gutenberg or Google Books or buy your own copy (you can even get some of titles as ebooks).

And could someone please expand that Wikipedia stub?

~~~

A PERFECT husband, who can find one?

For his price is far above gold bonds.

The grouch knoweth him not and his breakfast always pleaseth him. His mouth is filled with praises for his wife's cooking. He doth not expect chicken salad from left-over veal, neither the making of lobster patties from an ham-bone.

His wife is known within the gates, when she sitteth among the officers of her Club, by the fit of her gowns and her imported hats. He luncheth meagrely upon a sandwich that he may adorn her with fine jewels. He grumbleth not at the bills.

…

BEHOLD, my Daughter, the Lord maketh a man—but the wife maketh an husband.

For Man is but the raw material whereon a woman putteth the finishing touches.

Yea, and whatsoever pattern of husband thou selectest, thou shalt find him like unto a shop-made garment, which must be trimmed over and cut down, and ironed out, and built up to fit the matrimonial situation.

Verily, the best of husbands hath many raw edges, and many unnecessary pleats in his temper, and many wrinkles in his disposition, which must be removed.

~~~

This is a tiny sampling from The Sayings of Mrs. Solomon: Being the Confessions of the Seven Hundredth Wife as Revealed to Helen Rowland (1876-1950). Published in 1913, it’s online at Google Books or you can buy it at Amazon.

I discovered Helen Rowland in the newspaper (fittingly, since she was a journalist) via a Quote for the Day amusing enough to make me to look her up. Online one finds precious little. In addition to the very stubby stub in Wikipedia, there’s a brief (early) bio in a 1914 Woman's Who's Who of America. A 1928 New York Evening Journal booklet described her thusly:

HELEN ROWLAND, Author “Meditations of a Wife” Often referred to as America’s “Bernard Shaw,” and as America’s wittiest woman. Satire sparkles through her writings. Her observations on the foibles of men and women, the joys and sorrows of love and marriage, and the relief or the lack of it in divorce are always brilliant and entertaining, yet always “said with a smile.” Helen, like George Cohan, says: “I always leave ’em laughing when I say good-bye.”

Maybe the best way to get to know the eminently quotable Ms. Rowland is to read her—online at Project Gutenberg or Google Books or buy your own copy (you can even get some of titles as ebooks).

And could someone please expand that Wikipedia stub?

Tuesday, September 14, 2010

Stealing Kisses Inside Hats in 1810

Susan reports:

When we last saw the fashionable young Parisians of Le Supreme Bon Ton, they were swimming together with a vigorous freedom that seemed astonishing for 1810. Now the ladies and gentlemen are back on shore and dressed in their fashionable best, which, for the ladies, includes the new style of deep-brimmed hats. While the hats shown were doubtless exaggerated by this artist, the name given to the wearers ("the invisible ones") does imply that the wearer's face was well-hidden. Undaunted, the gentlemen seem determined to pursue the ladies inside their brims, and make the most of the privacy the hats provided – with clearly mixed results.

But while at first glance this print seems to be satirizing the fashionable headgear of the ladies, I believe the gentlemen, too, must be feeling the artist's sharpened barbs. Consider these amorous swains. Exactly how long must their necks be, that they'll be able to reach their ladies' lips for a kiss? And what misfortune has happened to their breeches? Over and over we read about the provocatively close-fitting breeches favored by young gentleman in this time period, and yet the ones these poor fellows are wearing are...not. 'Nuff said.

Except, of course, what's satirical sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, even in the land of the Bon Ton.

Above: Les invisibles en Tete-a-Tete, from the series Le Supreme Bon Ton, No. 16; artist unknown; published by Martinet, Paris, c. 1810-1815

Monday, September 13, 2010

Those poufy sleeves 1825-35

Loretta reports:

I’ve grown to love the puffy sleeves of the 1820s and 1830s, and their numerous names. We find gigot and imbecile and Béret sleeves and sleeves à l’Amadis, à la Donna Maria, à la Marino Falliéro, à la Sultane, à la Montespan, à la Caroline.

When you have stopped laughing, you might ask yourself how they managed the poufiness. Did the sleeves actually pouf as much as it seems in the pictures or are the artists taking artistic license? If the sleeves were as gigantic as they appear, how was this accomplished?

But maybe you’re not puzzled. Maybe you read my blog about the Green family estate auction, and noticed my remarks about the rare 1820s sleeves puffs (pictured above left).

I also learned that the sleeves might be lined with stiffened fabric, though I'm not clear on how this worked, exactly.

But now you may be wondering other things, like OMG, how could they stand to have padding (or stiffened fabric) in their sleeves? Indeed, the inconveniences of these sleeves is pointed out several times in the course of Last Night's Scandal, sometimes by my very fashionable heroine. I figure, they just suffered to be beautiful.

But another question is, How did those puff things work--were they sewn in or what?

I opened my trusty volume of Fashion in Detail 1730-1930 by Nancy Bradfield, with its meticulously detailed drawings. And there, on page 156, I found what I was looking for. “The tape ties inside the armhole are for securing the huge sleeve puffs, used 1825-1835.” Several other pages in the book show undergarments, including the sleeve puffs. Among these is a sketch of a figure from the Gallery of English Costume, Manchester, (U.K.) which rang a bell. In Blanche Payne’s History of Costume there’s a photograph of a woman wearing this typical underwear of 1825-1835. Her sleeve puffs are filled with down. I tried without success to find a link to the photo online. If you know what I'm talking about and have a link, please share!

I’ve grown to love the puffy sleeves of the 1820s and 1830s, and their numerous names. We find gigot and imbecile and Béret sleeves and sleeves à l’Amadis, à la Donna Maria, à la Marino Falliéro, à la Sultane, à la Montespan, à la Caroline.

When you have stopped laughing, you might ask yourself how they managed the poufiness. Did the sleeves actually pouf as much as it seems in the pictures or are the artists taking artistic license? If the sleeves were as gigantic as they appear, how was this accomplished?

But maybe you’re not puzzled. Maybe you read my blog about the Green family estate auction, and noticed my remarks about the rare 1820s sleeves puffs (pictured above left).

I also learned that the sleeves might be lined with stiffened fabric, though I'm not clear on how this worked, exactly.

But now you may be wondering other things, like OMG, how could they stand to have padding (or stiffened fabric) in their sleeves? Indeed, the inconveniences of these sleeves is pointed out several times in the course of Last Night's Scandal, sometimes by my very fashionable heroine. I figure, they just suffered to be beautiful.

But another question is, How did those puff things work--were they sewn in or what?

I opened my trusty volume of Fashion in Detail 1730-1930 by Nancy Bradfield, with its meticulously detailed drawings. And there, on page 156, I found what I was looking for. “The tape ties inside the armhole are for securing the huge sleeve puffs, used 1825-1835.” Several other pages in the book show undergarments, including the sleeve puffs. Among these is a sketch of a figure from the Gallery of English Costume, Manchester, (U.K.) which rang a bell. In Blanche Payne’s History of Costume there’s a photograph of a woman wearing this typical underwear of 1825-1835. Her sleeve puffs are filled with down. I tried without success to find a link to the photo online. If you know what I'm talking about and have a link, please share!

Sunday, September 12, 2010

Leafy History: The Beech Tree of Alexander Bane

Susan reports:

I live near Philadelphia, an area that fair bristles with historic landmark signs, but there's only one that I know that honors a tree. To be sure, it's a very old tree, an enormous European beech - Fagus sylvatica - whose gnarled serpentine branches spread and sprawl in every direction, and defied my attempts to fit it into a single photograph. The last time the tree was officially measured, in 2006, experts determined it to be more than 80 feet tall with a 90 foot spread and a trunk circumference of 190 inches, sufficient to earn designation as a Pennsylvania "Big Tree."

But since I'm a TNHG, it's the tree's past that fascinates me more than its size. According to the local historical society, the beech was planted around 1711, by a young Scottish-born farmer named Alexander Bane (1688-1747.) Not much is known of Alexander. He was a Friend, and he and his brother Mordecai both settled in what is now Chester County. In 1711, he purchased 300 acres of land that had been part of William Penn's original grant. Soon after, he planted this beech, perhaps as a reminder of the homeland he'd left behind, or perhaps to add a small touch of gentility to his new farm before he married a city-born bride from Philadelphia in 1713. Perhaps, too, the newly planted beech was included in his required "forest land"; aware of the majesty of colonial America (and aware, too, of how rapidly the once-great forests of England were disappearing), Penn stipulated that a portion of every settler's tract must remain uncleared and forested.

That's idle speculation, of course, and Friend Bane's reason for planting the beech is as lost as his farm. The farm was long ago broken up and "developed", the stone farmhouse torn down and the rolling fields around it replaced by suburban houses and an elementary school, with the four noisy lanes of Route 202 destroying any lingering hints of Quakerly peace.

Yet the tree remains. Now three hundred years old, it's an ancient but vital survivor, isolated and surrounded by a chain-link fence to protect it from nefarious teenagers and the tow-trucks headed for the auto repair shop across the street. Yet standing beneath its twisting branches, I think of how an elderly William Penn might have visited the Bane family's farm. He might well have sat on a nearby bench with Alexander, drinking cider poured by Jane Bane on a warm summer evening: the same William Penn who had refused to remove his hat before Charles II at Whitehall Palace, the same William Penn who received the generous grant of land in 1682 from James, Duke of York (who becomes the king of The Countess and the King ), that became Pennsylvania. In other words, this tree is a contemporary of the characters of my most recent books – and suddenly 17th c. England doesn't seem that long ago at all.

), that became Pennsylvania. In other words, this tree is a contemporary of the characters of my most recent books – and suddenly 17th c. England doesn't seem that long ago at all.

I live near Philadelphia, an area that fair bristles with historic landmark signs, but there's only one that I know that honors a tree. To be sure, it's a very old tree, an enormous European beech - Fagus sylvatica - whose gnarled serpentine branches spread and sprawl in every direction, and defied my attempts to fit it into a single photograph. The last time the tree was officially measured, in 2006, experts determined it to be more than 80 feet tall with a 90 foot spread and a trunk circumference of 190 inches, sufficient to earn designation as a Pennsylvania "Big Tree."

But since I'm a TNHG, it's the tree's past that fascinates me more than its size. According to the local historical society, the beech was planted around 1711, by a young Scottish-born farmer named Alexander Bane (1688-1747.) Not much is known of Alexander. He was a Friend, and he and his brother Mordecai both settled in what is now Chester County. In 1711, he purchased 300 acres of land that had been part of William Penn's original grant. Soon after, he planted this beech, perhaps as a reminder of the homeland he'd left behind, or perhaps to add a small touch of gentility to his new farm before he married a city-born bride from Philadelphia in 1713. Perhaps, too, the newly planted beech was included in his required "forest land"; aware of the majesty of colonial America (and aware, too, of how rapidly the once-great forests of England were disappearing), Penn stipulated that a portion of every settler's tract must remain uncleared and forested.

That's idle speculation, of course, and Friend Bane's reason for planting the beech is as lost as his farm. The farm was long ago broken up and "developed", the stone farmhouse torn down and the rolling fields around it replaced by suburban houses and an elementary school, with the four noisy lanes of Route 202 destroying any lingering hints of Quakerly peace.

Yet the tree remains. Now three hundred years old, it's an ancient but vital survivor, isolated and surrounded by a chain-link fence to protect it from nefarious teenagers and the tow-trucks headed for the auto repair shop across the street. Yet standing beneath its twisting branches, I think of how an elderly William Penn might have visited the Bane family's farm. He might well have sat on a nearby bench with Alexander, drinking cider poured by Jane Bane on a warm summer evening: the same William Penn who had refused to remove his hat before Charles II at Whitehall Palace, the same William Penn who received the generous grant of land in 1682 from James, Duke of York (who becomes the king of The Countess and the King

Shameless Self-Promotion: News on E-Books, & a Live Chat with Susan

Susan reports:

I've heard from readers this week who've felt neglected because The Countess & the King wasn't available digitally as an e-book. I'm happy to report that both Amazon and B&N.com are now offering e-book versions, so fire up those Nooks, Kindles, and iPads for near-instant downloading.

Also: Tomorrow evening, Monday, 13 September, I'll be participating in a live on-line author chat from 7:00-8:00 pm EST, and I'll be ready to answer (almost) any question you may pose. Click here for more details. Hope to see you there!

Thursday, September 9, 2010

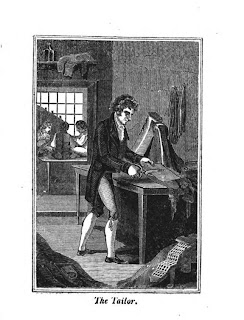

London Tailor 1818

Loretta reports:

Following is a short excerpt from a wonderful resource, The book of English trades: and library of the useful arts : with seventy engravings, by John Souter. 1818

THE TAILOR.

THE Tailor makes clothes for men and boys, and riding-habits for ladies.

In a tailor's shop, where much business is carried on, there are always two divisions of workmen: first, the foreman, who takes the measure of the person for whom the clothes are to be made, cuts out the cloth, and carries home the newly-finished garments to the customers. The others are mere working tailors, who sit cross-legged on the bench, like the man near the window, represented in the plate; of these, very few know how to cut out, with any degree of skill, the clothes which they sew together.

The tools requisite in the business of a tailor are very few and unexpensive: the sheers for the foreman, who stands to his work; for the others, a pair of scissors, a thimble, and needles of different sizes. In the thimble there is this peculiarity, that it is open at both ends. Besides these, there are required some long slips of parchment for measures, such as those represented hanging against the wall, and an iron, called a goose, with this, when made hot, they press down the scams, which would otherwise take off from the beauty of the goods. The stand of iron is generally a horse-shoe, rendered bright from use. Before the foreman, or master, (for where the trade is not extensive the master cuts out, measures gentlemen, and carries home the clothes,) is an open box, this contains buckram, tapes, bindings, trimmings, buttons, &c. with which every master-tailor should be furnished, and from which they derive very large profits. On the shelf is a piece of cloth ready to be made into clothes, and also a pattern-book.

....

A writer on this subject says, that a master-tailor ought to have a quick eye to steal the cut of a sleeve, the pattern of a flap, or the shape of a good trimming, at a glance : any bungler may cut out a shape when he has a pattern before him; but a good workman takes it by his eye in the passing of a chariot, or in the space between the door and a coach: he must be able not only to cut for the handsome and well-shaped, but bestow a good shape where nature has not granted it: he must make the clothes sit easy in spite of a stiff gait or awkward air : his hand and head must go together : he must be a nice cutter, and finish his work with elegance.

Following is a short excerpt from a wonderful resource, The book of English trades: and library of the useful arts : with seventy engravings, by John Souter. 1818

THE TAILOR.

THE Tailor makes clothes for men and boys, and riding-habits for ladies.

In a tailor's shop, where much business is carried on, there are always two divisions of workmen: first, the foreman, who takes the measure of the person for whom the clothes are to be made, cuts out the cloth, and carries home the newly-finished garments to the customers. The others are mere working tailors, who sit cross-legged on the bench, like the man near the window, represented in the plate; of these, very few know how to cut out, with any degree of skill, the clothes which they sew together.

The tools requisite in the business of a tailor are very few and unexpensive: the sheers for the foreman, who stands to his work; for the others, a pair of scissors, a thimble, and needles of different sizes. In the thimble there is this peculiarity, that it is open at both ends. Besides these, there are required some long slips of parchment for measures, such as those represented hanging against the wall, and an iron, called a goose, with this, when made hot, they press down the scams, which would otherwise take off from the beauty of the goods. The stand of iron is generally a horse-shoe, rendered bright from use. Before the foreman, or master, (for where the trade is not extensive the master cuts out, measures gentlemen, and carries home the clothes,) is an open box, this contains buckram, tapes, bindings, trimmings, buttons, &c. with which every master-tailor should be furnished, and from which they derive very large profits. On the shelf is a piece of cloth ready to be made into clothes, and also a pattern-book.

....

A writer on this subject says, that a master-tailor ought to have a quick eye to steal the cut of a sleeve, the pattern of a flap, or the shape of a good trimming, at a glance : any bungler may cut out a shape when he has a pattern before him; but a good workman takes it by his eye in the passing of a chariot, or in the space between the door and a coach: he must be able not only to cut for the handsome and well-shaped, but bestow a good shape where nature has not granted it: he must make the clothes sit easy in spite of a stiff gait or awkward air : his hand and head must go together : he must be a nice cutter, and finish his work with elegance.

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

Lucky Research: The Wedding Suit of James II

Susan reporting:

Loretta and I have often written here about the joys (and the challenges) of dressing our characters. Most times, we rely on a combination of contemporary sources, surviving examples, and imagination. But for one scene in The Countess & the King , I got lucky – really, really lucky. The embroidered suit that James Stuart (the King in the title), then Duke of York, wore to his second wedding over three hundred years ago miraculously still exists, and is on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; see it here.

, I got lucky – really, really lucky. The embroidered suit that James Stuart (the King in the title), then Duke of York, wore to his second wedding over three hundred years ago miraculously still exists, and is on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; see it here.

This suit has its own story to tell. James had it made for his wedding to his second wife in the winter of 1673, and like all royal weddings of the time, it was a political alliance, not a love match. The bride was a fifteen-year-old Italian princess, Mary Beatrice (her name already anglicized) of Modena. She was also Roman Catholic, and because James himself had recently converted to that faith as well, the wedding was wildly unpopular in Protestant England. In protest the princess was burned in straw effigies in London, as was James. A proxy wedding had already taken place in Modena, but the first time the couple were to meet would be when Mary Beatrice landed in Dover. Given England’s hostility, it was decided that the two should be wed in Dover, as quickly and quietly as possible.

Thus James’s suit was made of grey wool broadcloth to keep him warm as he stood on the winter beach. But the lining was a festive, bright coral ribbed silk (the waistcoat, now missing, was likely coral, too) and nearly every inch of the grey wool is covered with gold and silver embroidery, including the Garter Star (above) on the left breast. The embroidery design features intertwining lilies and honeysuckles, signifying purity and devoted love, both theoretically appropriate for a bridegroom, if not for James. The suit’s cut is the latest French fashion, and the style of the flopping oversized cuffs on the coat was called “hound’s-ears.” There are dozens of tiny decorative buttons, each wrapped in more gold thread; James’s wardrobe records show that he required 228 buttons for a complete suit of coat, waistcoat, and breeches!

It is easy to imagine him standing on the beach wearing it to greet his bride, the winter sun glinting on all that metallic embroidery. He wore the suit to their hasty marriage by the Bishop of Oxford in a private house in Dover, and again several days later when the newlyweds arrived at the palace in London, and James presented Mary Beatrice to his brother the king.

What happened next to the magnificent suit is especially interesting in light of Loretta's post yesterday. James presented the suit as a memento to Sir Edward Carteret, a loyal friend and supporter who had served as witness to the wedding. (Sir Edward's loyalty had been previously rewarded with a tidy tract of land along the American coast, known today as New Jersey.) After Sir Edward's death, the suit passed to his widow, then to her sister, wife of Matthew de Sausmarez. The suit remained at the Sausmarez Manor on the Isle of Guernsey for 320 years – until at last the family sold it at auction in 1992. (The cover of the Christie's catalogue is right.) Fortunately, the suit was acquired by the V& A, which has preserved it with great care for display, and also created an exact replica for study by history students.

But what was Mary Beatrice’s reaction to her well-dressed bridegroom? Exhausted from sea-sickness and her long journey, the princess reportedly took one look at James and burst into tears. So much for being a sharp-dressed man!

Many thanks to Chris Woodyard for the auction catalogue illustrations.

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

History on the Auction Block

Loretta reports:

The Green family was one of the Significant Families of Worcester, Massachusetts. I still regard them fondly because of Dr. John Green, who founded the Worcester Public Library (its early incarnation at left). His collection included some extremely rare and beautiful books—the sort NHGs expect to find only at big university libraries. Or in England at some duke’s place. Though not in this priceless category, some of the elderly volumes I consulted for Mr. Impossible bore Dr. Green’s name.

Then there was a Green Hill Park, where once upon a time, the family had lived in a great (for Massachusetts) estate. To my everlasting grief, the house, like so many others, was long gone by the time I discovered it, through old photographs. It included, I recently learned, a museum for the family. And now it turns out that some or all of this collection—art, furniture, furnishings, clothing, books, letters &c—ended up in the care of one lady. When she died, not long ago, the treasure trove went to descendants who do not strike me as being of the Nerdy History persuasion. My big clue was their nicknaming the experts evaluating their inheritance “antique geeks.” So I was troubled, but hardly surprised by their decision to sell off the lot.

Yes, it’s all being auctioned off this week, in the same city where that handsome estate with its private museum once stood. Here’s the story in the local paper.

I haven’t had time to go through all the catalogs. For sheer quantity, if not historical value, this reminds me of the auction of Horace Walpole’s estate. I did make time to check out the clothing—and it’s enough to make a Nerdy History Girl weep. Ye who are fascinated by historical dress will want to peruse this catalog. You’ll even find some of those pads they used to pouf out sleeves in the 1820s and 1830s!

If you’ve got some time on your hands, you can examine all the catalogs at the auctioneer’s site. Or you can hurry on over to the DCU center in Worcester and bid on something.

But before or after that, would you tell me something? If you were the one who inherited all this stuff, what would you do?

Monday, September 6, 2010

Intrepid Women: Katherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester

Susan reports:

Whenever we post about a historical Intrepid Lady, we always see at least one comment about how that lady's story would make a fantastic book. Today I'm heading the comments off at the proverbial pass, because this Intrepid Lady is the heroine of my brand-new historical novel The Countess and the King.

Though only a footnote in most histories, Katherine Sedley (1657-1717) deserves more than that. True, she didn't change the course of history, or create or inspire great works of art. But she was wickedly funny, independent, and unpredictable, and determined to go her own way, which very few other well-bred 17th c. ladies dared to do.