Loretta reports:

From The Every-day book; or, Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, Vol. II, by William Hone.

~~~

September 1*

Until this day partridges are protected by act of parliament from those who are "privileged to kill."

Application for a License.

In the shooting season of 1821, a fashionably dressed young man applied to sir Robert Baker for a license to kill— not game, but thieves. This curious application was made in the most serious and business-like manner imaginable.

"Can I be permitted to speak a few words to you, sir?" said the applicant. "Certainly, sir," replied sir Robert. " Then I wish to ask you, sir, whether, if I am attacked by thieves in the streets or roads, I should be justified in using fire-arms against them, and putting them to death ?" Sir Robert Baker replied, that every man had a right to defend himself from robbers in the best manner he could; but at the same time he would not be justified in using fire-arms, except in cases of the utmost extremity. "Oh! I am very much obliged to you, sir; and I can be furnished at this office with a license to carry arms for that purpose?" The answer, of course, was given in the negative, though not without a good deal of surprise at such a question, and the inquirer bowed and withdrew.

* Feast of St. Giles, patron saint of beggars and blacksmiths, among many others. The name is familiar to Regency readers as a famously crime-ridden section of London.

Illustration by Robert Havell, Partridge Shooting at Windsor.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Happy Birthday to Us!

Loretta and Susan reporting:

Today* we are one!

That is, not us specifically (even if we are both Geminis), but our blog. When we began the Two Nerdy History Girls last year, we decided to write what we wanted to read, and hope that might be a few others out there who might like to read it, too. Turns out there are a great many of you: we've had over 100,000 page views, and our 250th follower just signed up this week. We're delighted that we've delighted you. Long live Nerdy Girl History, and many, many thanks for your support and your enthusiasm, your interest and your comments!

* We realize that there may be those who will quibble with this birthday, since a few posts in our archive date from earlier in the summer of 2009. These were our trial blogs, shared with a small, trusted, and indulgent audience while we were trying to figure out what the hoo-hah we were actually doing. We went live to the world on September 1, 2009, which is why we decided that was our true birthday. Besides, if the Queen of England can celebrate her birthday in June because the weather's better, we figured we could choose September 1.

Today* we are one!

That is, not us specifically (even if we are both Geminis), but our blog. When we began the Two Nerdy History Girls last year, we decided to write what we wanted to read, and hope that might be a few others out there who might like to read it, too. Turns out there are a great many of you: we've had over 100,000 page views, and our 250th follower just signed up this week. We're delighted that we've delighted you. Long live Nerdy Girl History, and many, many thanks for your support and your enthusiasm, your interest and your comments!

* We realize that there may be those who will quibble with this birthday, since a few posts in our archive date from earlier in the summer of 2009. These were our trial blogs, shared with a small, trusted, and indulgent audience while we were trying to figure out what the hoo-hah we were actually doing. We went live to the world on September 1, 2009, which is why we decided that was our true birthday. Besides, if the Queen of England can celebrate her birthday in June because the weather's better, we figured we could choose September 1.

Monday, August 30, 2010

Intrepid Women: Sarah Bowdich Quells a Mutiny, 1816

Susan reporting:

In 1816, not all English ladies were leading a genteel, Austen-esque life in the country. At least one of them was sailingwith her infant daughter to Africa to meet her husband. Sarah Wallis Bowdich (1791-1856) was the only woman, let alone the only lady, on board a small merchant ship full of desperate men. Here's Sarah's own telling of what happened one evening, from her 1835 book Stories of Strange Lands, & Fragments from the Notes of a Traveller:

The surgeon whispered to me his apprehensions that all was not well, and that our people...were irritated and annoyed, and in a most discontented state. The first mate was in command of the vessel; and, though he was an admirable sailor, and a most obliging and excellent person, was very impetuous. The dinner was sent to table very ill-dressed, and the cook was summoned aft to receive a reprimand. He became impertinent, and the mate, seizing a butter-boat, threw it at his head....A general scuffle ensued, and the second mate, running to the chest of arms, loaded a brace of pistols, and stood in the door-way of the cabin, swearing to two men who came aft, that he would blow their brains out if they ventured a step further. I expostulated with him, but he only replied, "You do not know the danger, Ma'am; the men are in a state of mutiny, and if they seize on the small-arms, we may all be murdered." My child happened to be on deck; and, at the word murdered, I crept under the second mate's arm after her. She was perfectly safe, with Antonio [another sailor] beside her, as guard. My fellow-passenger [a convicted slaver!] was on the larboard side, striving by fair words to quell the tumult; but the first mate was nearly overpowered at the opposite gangway. In striving to reach my child, I became mixed up with their party; and, without knowing it, was close by the mate when when the cook made a plunge at him with the large knife with which he cut the meat. To seize the cook's arm, to snatch the knife out of his hand, and throw it into the sea, was an affair of impulse, not reflection; however, it probably saved the mate, for the knife had already cut through his waistcoat. This action, and my presence, seemed to produce a momentary pause, and gave time to those who were well-disposed to rally round their master. The cook was put in irons, and...went away muttering curses and threats; and I had no inclination to eat the offering with which he had tried to propitiate me....I accordingly threw it into the sea, and retired to the cabin, to prevent further identification with this painful concern.

But wait! This is only one tiny slice of this lady's amazing and accomplished life. More, much more, to follow on Thursday....

Above: Loaded pistols were served out to all the sure men by N.C. Wyeth, 1911, illustration for Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, Collection of Andrew and Betsy Wyeth.

In 1816, not all English ladies were leading a genteel, Austen-esque life in the country. At least one of them was sailingwith her infant daughter to Africa to meet her husband. Sarah Wallis Bowdich (1791-1856) was the only woman, let alone the only lady, on board a small merchant ship full of desperate men. Here's Sarah's own telling of what happened one evening, from her 1835 book Stories of Strange Lands, & Fragments from the Notes of a Traveller:

The surgeon whispered to me his apprehensions that all was not well, and that our people...were irritated and annoyed, and in a most discontented state. The first mate was in command of the vessel; and, though he was an admirable sailor, and a most obliging and excellent person, was very impetuous. The dinner was sent to table very ill-dressed, and the cook was summoned aft to receive a reprimand. He became impertinent, and the mate, seizing a butter-boat, threw it at his head....A general scuffle ensued, and the second mate, running to the chest of arms, loaded a brace of pistols, and stood in the door-way of the cabin, swearing to two men who came aft, that he would blow their brains out if they ventured a step further. I expostulated with him, but he only replied, "You do not know the danger, Ma'am; the men are in a state of mutiny, and if they seize on the small-arms, we may all be murdered." My child happened to be on deck; and, at the word murdered, I crept under the second mate's arm after her. She was perfectly safe, with Antonio [another sailor] beside her, as guard. My fellow-passenger [a convicted slaver!] was on the larboard side, striving by fair words to quell the tumult; but the first mate was nearly overpowered at the opposite gangway. In striving to reach my child, I became mixed up with their party; and, without knowing it, was close by the mate when when the cook made a plunge at him with the large knife with which he cut the meat. To seize the cook's arm, to snatch the knife out of his hand, and throw it into the sea, was an affair of impulse, not reflection; however, it probably saved the mate, for the knife had already cut through his waistcoat. This action, and my presence, seemed to produce a momentary pause, and gave time to those who were well-disposed to rally round their master. The cook was put in irons, and...went away muttering curses and threats; and I had no inclination to eat the offering with which he had tried to propitiate me....I accordingly threw it into the sea, and retired to the cabin, to prevent further identification with this painful concern.

But wait! This is only one tiny slice of this lady's amazing and accomplished life. More, much more, to follow on Thursday....

Above: Loaded pistols were served out to all the sure men by N.C. Wyeth, 1911, illustration for Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, Collection of Andrew and Betsy Wyeth.

Following Up: Ann Thicknesse to Shine in Cincinnati

Susan reporting:

Earlier this year, we wrote of one of our favorite Intrepid Women, the celebrated musician Ann Ford Thicknesse (1737-1834). Thanks to our friends at the Duchess of Devonshire's Gossip Guide, we've learned that Mrs. Thicknesse's fabulous portrait (left) by Thomas Gainsborough has been newly spruced, and will be the centerpiece of a show this fall at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Thomas Gainsborough and the Modern Woman promises not only extraordinary paintings, but gowns of the Georgian period as well. If you're fortunate enough to be in Ohio this fall (the show runs September 18-January 2), we hope you'll stop by and pay your respects to Mrs. Thicknesse. She is quite deserving.

Above: Mrs. Philip Thicknesse, nee Ann Ford, by Thomas Gainsborough, 1760, Cincinnati Art Museum

Earlier this year, we wrote of one of our favorite Intrepid Women, the celebrated musician Ann Ford Thicknesse (1737-1834). Thanks to our friends at the Duchess of Devonshire's Gossip Guide, we've learned that Mrs. Thicknesse's fabulous portrait (left) by Thomas Gainsborough has been newly spruced, and will be the centerpiece of a show this fall at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Thomas Gainsborough and the Modern Woman promises not only extraordinary paintings, but gowns of the Georgian period as well. If you're fortunate enough to be in Ohio this fall (the show runs September 18-January 2), we hope you'll stop by and pay your respects to Mrs. Thicknesse. She is quite deserving.

Above: Mrs. Philip Thicknesse, nee Ann Ford, by Thomas Gainsborough, 1760, Cincinnati Art Museum

Sunday, August 29, 2010

Riding Habit 1817

Loretta reports:

I'm always thrilled to find riding habits and court dresses in the fashion magazines, because these are not nearly so common as evening dresses and walking dresses. This is one very like what I had imagined my heroine Zoe (of Don't Tempt Me) wearing.

I cannot pin down the "Glengary" element, since it doesn't correspond with definitions I've found elsewhere, including Louis Harmuth's 1915 Dictionary of Textiles. The cap doesn't look like today's idea of a Glengarry cap, and, being made of satin, doesn't fit the "mottled wool" definition below. Perhaps one of our knowledgeable readers can enlighten us.

From Ackermann's Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c., The Second Series, Vol. IV. September 1, 1817. No. XXI

~~~~~

*Glengarry—All-wool, mottled English tweed. (?????)

**Cloth—1, general term for fulled woolen fabrics; 2, general term for any textile fabric having some body; 3, medieval English worsted made six yards long and two yards wide.

I'm always thrilled to find riding habits and court dresses in the fashion magazines, because these are not nearly so common as evening dresses and walking dresses. This is one very like what I had imagined my heroine Zoe (of Don't Tempt Me) wearing.

I cannot pin down the "Glengary" element, since it doesn't correspond with definitions I've found elsewhere, including Louis Harmuth's 1915 Dictionary of Textiles. The cap doesn't look like today's idea of a Glengarry cap, and, being made of satin, doesn't fit the "mottled wool" definition below. Perhaps one of our knowledgeable readers can enlighten us.

From Ackermann's Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c., The Second Series, Vol. IV. September 1, 1817. No. XXI

~~~~~

PLATE 16.—THE GLENGARY* HABIT

Is composed of the finest pale blue cloth,** and richly ornamented with frogs and braiding to correspond. The front, which is braided on each side, fastens under the body of the habit, which slopes down on each side in a very novel style, and in such a manner as to form the shape to considerable advantage. The epaulettes and jacket are braided to correspond with the front, as is also the bottom of the sleeve, which is braided nearly half way up the arm. Habit-shirt, composed of cambric, with a high standing collar, trimmed with lace. Cravat of soft muslin, richly worked at the ends, and tied in a full bow. Narrow lace ruffles. Head-dress, the Glengary cap, composed of blue satin, and trimmed with plaited ribbon of various shades of blue, and a superb plume of feathers. Blue kid gloves, and half-boots.

Is composed of the finest pale blue cloth,** and richly ornamented with frogs and braiding to correspond. The front, which is braided on each side, fastens under the body of the habit, which slopes down on each side in a very novel style, and in such a manner as to form the shape to considerable advantage. The epaulettes and jacket are braided to correspond with the front, as is also the bottom of the sleeve, which is braided nearly half way up the arm. Habit-shirt, composed of cambric, with a high standing collar, trimmed with lace. Cravat of soft muslin, richly worked at the ends, and tied in a full bow. Narrow lace ruffles. Head-dress, the Glengary cap, composed of blue satin, and trimmed with plaited ribbon of various shades of blue, and a superb plume of feathers. Blue kid gloves, and half-boots.

*Glengarry—All-wool, mottled English tweed. (?????)

**Cloth—1, general term for fulled woolen fabrics; 2, general term for any textile fabric having some body; 3, medieval English worsted made six yards long and two yards wide.

Thursday, August 26, 2010

The Noisy Height of Fashion: Slap Sole Shoes

Susan reporting:

We NHG do love shoes, and this pair must have been right on the cutting edge of fashion when they were new, the must-have Louboutins of 17th c. London.

Like many extreme fashions, slap soles evolved from a useful idea. Earlier in the century, gentlemen would slip flat-soled mules over their riding boots to prevent the heels from sinking into the muddy ground of stable yards. Some enterprising shoemaker took the idea a step further, and put the flat sole beneath a pair of lady's high heels, and the slap sole was born. While the sole is connected to the front of the shoe, the part beneath the heel is not, which made for a clacking, slapping sound as the lady walked. I'm guessing the slap sole was also easier to walk in, much as a tall wedge offers more support than a narrow stiletto (first-hand NHG research at work!) But that distinctive clack on the bare floors of the time must have been gratifying indeed to the wearer, letting all around her know that she had the "it" shoes of the season, even if they were hidden beneath her sweeping petticoats.

In addition to the slap soles, these shoes feature an extended square toe that overhangs the sole (much like the current island platforms.) The shoes are made from fine white kid that never would have gone near a muddy stable yard. The heels are very high for the time, much higher than most ladies would dare. The gold braid and bright pink silk ribbon trimming has faded, and the wide pink ribbons through the latchets that would have been tied into extravagant bows are missing. But the magical allure of these shoes remains, and it's easy to imagine them climbing the stairs in Whitehall Palace.

Here are two more examples of slap soles: an Italian pair, trimmed with silver and gold lace, and another English pair said to have been a royal gift from Charles II.

Above: Slap Sole Shoes, c. 1650-1670, English. Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto.

We NHG do love shoes, and this pair must have been right on the cutting edge of fashion when they were new, the must-have Louboutins of 17th c. London.

Like many extreme fashions, slap soles evolved from a useful idea. Earlier in the century, gentlemen would slip flat-soled mules over their riding boots to prevent the heels from sinking into the muddy ground of stable yards. Some enterprising shoemaker took the idea a step further, and put the flat sole beneath a pair of lady's high heels, and the slap sole was born. While the sole is connected to the front of the shoe, the part beneath the heel is not, which made for a clacking, slapping sound as the lady walked. I'm guessing the slap sole was also easier to walk in, much as a tall wedge offers more support than a narrow stiletto (first-hand NHG research at work!) But that distinctive clack on the bare floors of the time must have been gratifying indeed to the wearer, letting all around her know that she had the "it" shoes of the season, even if they were hidden beneath her sweeping petticoats.

In addition to the slap soles, these shoes feature an extended square toe that overhangs the sole (much like the current island platforms.) The shoes are made from fine white kid that never would have gone near a muddy stable yard. The heels are very high for the time, much higher than most ladies would dare. The gold braid and bright pink silk ribbon trimming has faded, and the wide pink ribbons through the latchets that would have been tied into extravagant bows are missing. But the magical allure of these shoes remains, and it's easy to imagine them climbing the stairs in Whitehall Palace.

Here are two more examples of slap soles: an Italian pair, trimmed with silver and gold lace, and another English pair said to have been a royal gift from Charles II.

Above: Slap Sole Shoes, c. 1650-1670, English. Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto.

NHG Library: Dolls' Houses

Loretta reports:

Among the fascinating little books I’ve received from Shire Library, one of my current favorites is Dolls’ Houses by Halina Pasierbska.

Don’t know about you, but I love doll houses, and finding one in a museum or historic house is a special delight. One that hasn’t been refurnished over the years offers a peep into the past. It's not just one room in a painting or drawing, but a cross section of an entire house, complete with furniture arrangements that suggest how the space might actually have been used. Since historically accurate illustrations of household interiors are not as abundant as exteriors, a doll house can be a helpful research tool.

And even if they’ve nothing to do with my chosen historical period, they’re just fascinating to study. The Shire book shows us doll houses from the 17th to 20th century, some of which are in private collections.

Among many other things, I learned that the terms “Baby House” and “Doll House” referred to size, not purpose. I was less surprised to learn that they were not regarded simply as toys. “It would seem,” writes Ms. Pasierbska, “that the houses…served a serious instructional purpose as well as being objects which reflected the wealth of their owners. They were excellent visual aids which helped young girls of the privileged classes to learn, through play, how to become good household managers.”

It’s a lovely little book, packing a lot of info into a small package and providing, as Shire books generally do, not only a list of further reading, but of places to visit.

Want more doll houses? Click on the links to take a tour of The Doll's House of Petronella Oortman (late 17th C), Queen Mary’s Doll House, or Colleen Moore’s Fairy Castle.

Illustration is from the book: Bedroom on the first floor of the Stromer House, 1639.

And here, in accord with some FTC rule or other (which probably doesn’t apply to us, since we're not reviewers, but never mind), I need to tell you that, unlike the majority of books referred to in this blog, which Susan and I buy with our own hard-earned cash, this one came gratis.

Among the fascinating little books I’ve received from Shire Library, one of my current favorites is Dolls’ Houses by Halina Pasierbska.

Don’t know about you, but I love doll houses, and finding one in a museum or historic house is a special delight. One that hasn’t been refurnished over the years offers a peep into the past. It's not just one room in a painting or drawing, but a cross section of an entire house, complete with furniture arrangements that suggest how the space might actually have been used. Since historically accurate illustrations of household interiors are not as abundant as exteriors, a doll house can be a helpful research tool.

And even if they’ve nothing to do with my chosen historical period, they’re just fascinating to study. The Shire book shows us doll houses from the 17th to 20th century, some of which are in private collections.

Among many other things, I learned that the terms “Baby House” and “Doll House” referred to size, not purpose. I was less surprised to learn that they were not regarded simply as toys. “It would seem,” writes Ms. Pasierbska, “that the houses…served a serious instructional purpose as well as being objects which reflected the wealth of their owners. They were excellent visual aids which helped young girls of the privileged classes to learn, through play, how to become good household managers.”

It’s a lovely little book, packing a lot of info into a small package and providing, as Shire books generally do, not only a list of further reading, but of places to visit.

Want more doll houses? Click on the links to take a tour of The Doll's House of Petronella Oortman (late 17th C), Queen Mary’s Doll House, or Colleen Moore’s Fairy Castle.

Illustration is from the book: Bedroom on the first floor of the Stromer House, 1639.

And here, in accord with some FTC rule or other (which probably doesn’t apply to us, since we're not reviewers, but never mind), I need to tell you that, unlike the majority of books referred to in this blog, which Susan and I buy with our own hard-earned cash, this one came gratis.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Putting the Pineapple in its Proper Place

Susan reporting:

This is one of my favorite paintings of Charles II. I like it primarily because he's dressed in the expensive but restrained style and sober colors that he preferred for everyday, rather than in those over-the-top robes of state. I also like it because it's a quirky picture. Kings are always being presented with gifts, and here Charles and a couple of his numerous spaniels are receiving not a priceless jewel or golden trinket, but a pineapple. The giver is John Rose, the royal gardener, and his offering is proof of the rarity and value of pineapples in 17th c. England. The pineapple had earlier been brought to Europe from the Caribbean by Columbus, but it remained an exotic treat, grown only with care in greenhouses, and, apparently, by royal gardeners.

All that makes sense, history-wise. But sometimes the caption on this picture includes a bit more, about how the pineapple represents Charles's reputation for royal hospitality. Most of us would accept that, too. Everyone knows the pineapple as a symbol for hospitality. The fruit turns up everywhere, from cocktail napkins to Christmas decorations, always waving its spiky top in welcome.

But it turns out all those holiday napkins are wrong. One of my favorite history blogs, History Myths Debunked, recently performed a most thorough debunking of the hospitable pineapple. Seems that while pineapples do turn up as 17th and 18th c. decorative motifs, they're used for their exoticism rather than as official greeters. More perplexing is how Dionysian pine cones are often mistaken for pineapples – though I have to admit the examples are convincing.

Even the most famous pineapple in 18th c. Britain – the Earl of Dunmore's fanciful 1761 garden pavilion (above right) – has been included in the debunking. A birthday present for the countess, the pavilion was designed to represent power and wealth, not hospitality. As one commentator notes, "The earl built it because he could." The pineapple on the tower reflected the hothouse on the ground floor, where pineapples were in fact grown for the kitchens of Dunmore House.

So there it is: the truth about historical pineapples. But whether pineapples are welcoming or not, I have to think that the guests of both Charles II and the Countess of Dunmore were mightily pleased when, on a chilly winter night in London or Scotland, this golden taste of the tropics appeared on the supper table.

Top: Charles II Receiving a Pineapple by Hendrik Danckerts, 1675. Copy of an original in the Royal Collection.

Lower right: The Dunmore Pineapple, 1761, Dunmore Park, Airth, Scotland

This is one of my favorite paintings of Charles II. I like it primarily because he's dressed in the expensive but restrained style and sober colors that he preferred for everyday, rather than in those over-the-top robes of state. I also like it because it's a quirky picture. Kings are always being presented with gifts, and here Charles and a couple of his numerous spaniels are receiving not a priceless jewel or golden trinket, but a pineapple. The giver is John Rose, the royal gardener, and his offering is proof of the rarity and value of pineapples in 17th c. England. The pineapple had earlier been brought to Europe from the Caribbean by Columbus, but it remained an exotic treat, grown only with care in greenhouses, and, apparently, by royal gardeners.

All that makes sense, history-wise. But sometimes the caption on this picture includes a bit more, about how the pineapple represents Charles's reputation for royal hospitality. Most of us would accept that, too. Everyone knows the pineapple as a symbol for hospitality. The fruit turns up everywhere, from cocktail napkins to Christmas decorations, always waving its spiky top in welcome.

But it turns out all those holiday napkins are wrong. One of my favorite history blogs, History Myths Debunked, recently performed a most thorough debunking of the hospitable pineapple. Seems that while pineapples do turn up as 17th and 18th c. decorative motifs, they're used for their exoticism rather than as official greeters. More perplexing is how Dionysian pine cones are often mistaken for pineapples – though I have to admit the examples are convincing.

Even the most famous pineapple in 18th c. Britain – the Earl of Dunmore's fanciful 1761 garden pavilion (above right) – has been included in the debunking. A birthday present for the countess, the pavilion was designed to represent power and wealth, not hospitality. As one commentator notes, "The earl built it because he could." The pineapple on the tower reflected the hothouse on the ground floor, where pineapples were in fact grown for the kitchens of Dunmore House.

So there it is: the truth about historical pineapples. But whether pineapples are welcoming or not, I have to think that the guests of both Charles II and the Countess of Dunmore were mightily pleased when, on a chilly winter night in London or Scotland, this golden taste of the tropics appeared on the supper table.

Top: Charles II Receiving a Pineapple by Hendrik Danckerts, 1675. Copy of an original in the Royal Collection.

Lower right: The Dunmore Pineapple, 1761, Dunmore Park, Airth, Scotland

Monday, August 23, 2010

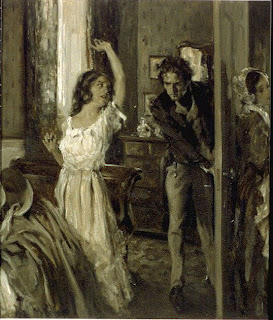

One Angry Wife

Loretta reports:

What do you think, Gentle Reader: Can this marriage be saved?

~~~

From La Belle Assemblée, Vol. 3, 1807

DEFINITION OF A HUSBAND BY HIS WIFE.

THIS lady composed the following vocabulary to express the character of a husband, from her own experience, and which proves how copious our language is on that article:—He is, said she, an abhorred, abominable, acrimonious, angry, arrogant, austere, awkward, barbarous, bitter, blustering, boisterous, boorish, brawling, brutal, bullying, capricious, captious, careless, choleric, churlish, clamorous, contumelious, crabbed, cross, currish, detestable, disagreeable, discontented, disgusting, dismal, dreadful, drowsy, dry, dull, envious, execrable, fastidious, fierce, fretful, froward, frumpish, furious, grating, gross, growling, gruff, grumbling, hard-hearted, hasty, hateful, hectoring, horrid, huffish, humoursome, illiberal, ill natured, implacable, inattentive, incorrigible, inflexible, injurious, insolent, intractable, irascible, ireful, jealous, keen, loathsome, maggotty, malevolent, malicious, malignant, maundering, mischievous, morose, murmuring, nauseous, nefarious, negligent, noisy, obstinate, obstreperous, odious, offensive, opinionated, oppressive, outrageous, overbearing, passionate, peevish, pervicacious, perverse, perplexing, pettish, petulant, plaguy, quarrelsome, queasy, queer, raging, restless, rigid, rigorous, roaring, rough, rude, rugged, saucy, savage, severe, sharp, shocking, sluggish, snappish, snarling, sneaking, sour, spiteful, splenetic, squeamish, stern, stubborn, stupid, sulky, sullen, surly, suspicious, tantalizing, tart, teasing, terrible, testy, tiresome, tormenting, touchy, treacherous, troublesome, turbulent, tyrannicaI, uncomfortable, ungovernable, unpleasant, unsuitable, uppish, vexatious, violent, virulent, waspish, worrying, wrangling, wrathful, yarring, yelping dog in a manger, who neither eats himself nor will let others eat.

~~~~~~~~

Illustration: Get out, will you, she stormed, by Arthur Ignatius Keller[1922?], courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

What do you think, Gentle Reader: Can this marriage be saved?

~~~

From La Belle Assemblée, Vol. 3, 1807

DEFINITION OF A HUSBAND BY HIS WIFE.

THIS lady composed the following vocabulary to express the character of a husband, from her own experience, and which proves how copious our language is on that article:—He is, said she, an abhorred, abominable, acrimonious, angry, arrogant, austere, awkward, barbarous, bitter, blustering, boisterous, boorish, brawling, brutal, bullying, capricious, captious, careless, choleric, churlish, clamorous, contumelious, crabbed, cross, currish, detestable, disagreeable, discontented, disgusting, dismal, dreadful, drowsy, dry, dull, envious, execrable, fastidious, fierce, fretful, froward, frumpish, furious, grating, gross, growling, gruff, grumbling, hard-hearted, hasty, hateful, hectoring, horrid, huffish, humoursome, illiberal, ill natured, implacable, inattentive, incorrigible, inflexible, injurious, insolent, intractable, irascible, ireful, jealous, keen, loathsome, maggotty, malevolent, malicious, malignant, maundering, mischievous, morose, murmuring, nauseous, nefarious, negligent, noisy, obstinate, obstreperous, odious, offensive, opinionated, oppressive, outrageous, overbearing, passionate, peevish, pervicacious, perverse, perplexing, pettish, petulant, plaguy, quarrelsome, queasy, queer, raging, restless, rigid, rigorous, roaring, rough, rude, rugged, saucy, savage, severe, sharp, shocking, sluggish, snappish, snarling, sneaking, sour, spiteful, splenetic, squeamish, stern, stubborn, stupid, sulky, sullen, surly, suspicious, tantalizing, tart, teasing, terrible, testy, tiresome, tormenting, touchy, treacherous, troublesome, turbulent, tyrannicaI, uncomfortable, ungovernable, unpleasant, unsuitable, uppish, vexatious, violent, virulent, waspish, worrying, wrangling, wrathful, yarring, yelping dog in a manger, who neither eats himself nor will let others eat.

~~~~~~~~

Illustration: Get out, will you, she stormed, by Arthur Ignatius Keller[1922?], courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Sunday, August 22, 2010

A French Lady Languishing in her Boudoir in 1693

Susan reporting:

There has always been something special about how Frenchwomen dress, an undeniable, inborn sense of style. This is nothing new. Loretta's numerous fashion plates have proved that Paris was the fashion capitol long before Coco Chanel was born. In 45 B.C. while Julius Caesar was writing "All Gaul is divided into three parts," Mrs. Caesar was doubtless asking "Yes, but what are the Gallic ladies wearing?"

But while the exact origins of French fashion are hazy, the first appearance French fashion journalism has a definite date. The Mercure galant first appeared in 1672, and its goal was fresh and new: to report the latest news from Parisian society, including theater reviews, poems, social news of marriages, gossip, and, of course, fashion. In short, it was the first journal to focus entirely on the lifestyles of the rich and famous, especially the rich and famous at the royal court of Louis XIV. All this important news would be delivered with the swiftness of Mercury (the "Mercure" of the title), the messenger of the gods, and ladies and would-be ladies in every corner of France as well as the rest of Europe waited breathlessly for each issue.

This illustration from September, 1693, showed that the editors had already determined the formula that modern 'zines use today. The picture is by a notable engraver of the time, Jean Dieu de St Jean, and it offers that unbeatable combination of fashion and sex. It's easy to see what's in store from the title alone: Femme de qualite en deshabille neglige, which translates roughly as "a lady of quality in casual undress."

That's exactly what it is, too: a lady in her bedchamber or boudoir, dressed for relaxing and, perhaps, seduction. She's wearing a luxurious silk dressing gown left open over her richly embroidered smock, and her stays (corset) are loosely laced across the front for casual wear. But those stays still manage to provide a generous display of her bare breasts, and more shocking still are her crossed legs. Crossed ankles would have been daring enough for a 17th c. lady, but for her to cross her knees, revealing both the shape of her thighs – her thighs! – as well as her entire ankle, foot, and tiny, pointed mule with its high curving heel must have defined "titillation" to readers. It's clear enough that her smock rests on her bare skin, without any of the usual protective layers of petticoats.

Perhaps the editors were a bit uneasy by how much the lady revealed, because the illustration's caption included fictional foolishness to explain her disarray. Supposedly the artist "imagined that the lady had just read a distressing letter; this is evident from the expression on her face and from the rest of her pose."

Well, whatever. But given the lady's artful lace headdress, the seductively placed black velvet patches on her face, and those delicious little shoes, I'm betting she won't be suffering alone for long....

Above: Femme de qualite en deshabille neglige, engraving by Jean Dieu de St Jean for Mercure galant, 1693

There has always been something special about how Frenchwomen dress, an undeniable, inborn sense of style. This is nothing new. Loretta's numerous fashion plates have proved that Paris was the fashion capitol long before Coco Chanel was born. In 45 B.C. while Julius Caesar was writing "All Gaul is divided into three parts," Mrs. Caesar was doubtless asking "Yes, but what are the Gallic ladies wearing?"

But while the exact origins of French fashion are hazy, the first appearance French fashion journalism has a definite date. The Mercure galant first appeared in 1672, and its goal was fresh and new: to report the latest news from Parisian society, including theater reviews, poems, social news of marriages, gossip, and, of course, fashion. In short, it was the first journal to focus entirely on the lifestyles of the rich and famous, especially the rich and famous at the royal court of Louis XIV. All this important news would be delivered with the swiftness of Mercury (the "Mercure" of the title), the messenger of the gods, and ladies and would-be ladies in every corner of France as well as the rest of Europe waited breathlessly for each issue.

This illustration from September, 1693, showed that the editors had already determined the formula that modern 'zines use today. The picture is by a notable engraver of the time, Jean Dieu de St Jean, and it offers that unbeatable combination of fashion and sex. It's easy to see what's in store from the title alone: Femme de qualite en deshabille neglige, which translates roughly as "a lady of quality in casual undress."

That's exactly what it is, too: a lady in her bedchamber or boudoir, dressed for relaxing and, perhaps, seduction. She's wearing a luxurious silk dressing gown left open over her richly embroidered smock, and her stays (corset) are loosely laced across the front for casual wear. But those stays still manage to provide a generous display of her bare breasts, and more shocking still are her crossed legs. Crossed ankles would have been daring enough for a 17th c. lady, but for her to cross her knees, revealing both the shape of her thighs – her thighs! – as well as her entire ankle, foot, and tiny, pointed mule with its high curving heel must have defined "titillation" to readers. It's clear enough that her smock rests on her bare skin, without any of the usual protective layers of petticoats.

Perhaps the editors were a bit uneasy by how much the lady revealed, because the illustration's caption included fictional foolishness to explain her disarray. Supposedly the artist "imagined that the lady had just read a distressing letter; this is evident from the expression on her face and from the rest of her pose."

Well, whatever. But given the lady's artful lace headdress, the seductively placed black velvet patches on her face, and those delicious little shoes, I'm betting she won't be suffering alone for long....

Above: Femme de qualite en deshabille neglige, engraving by Jean Dieu de St Jean for Mercure galant, 1693

Thursday, August 19, 2010

A glimpse of London in 1827

Loretta reports:

One of my favorite sources of historical information is the tourist guidebook. The following excerpt is from the 1827 edition of Leigh's new picture of London: or A view of the political, religious, medical, literary, municipal, commercial, and moral state of the British metropolis.

~~~~~

All the streets of London are paved with great regularity, and have a foot-path, laid with flags, divided from the carriage-way: the latter is formed by small square blocks of Scotch granite. The foot-path has a regular curb stone, raised some inches above the carriage-way; of course the accommodation to the foot passenger must depend upon the breadth of the avenue: but as every alteration for many years past, has tended to widen the streets and lanes of the metropolis, the narrow avenues which admit carriages are gradually increasing in convenience to the pedestrian. In 1823, a new method of forming the carriage-ways of London was commenced in St. James's Square, under the superintendence of Mr. McAdam. By this process, which consists of breaking the stones into small pieces of the same size, it is hoped that a more level road will be obtained than the old pavement. Nearly all the streets are lighted by gas, an improvement which has only been introduced within a few years.

The Climate of London is temperate, but variable and inclined to moisture. The average temperature is 51° 9', although it varies from 20° to 81° the greatest cold usually occurring in January, and the greatest heat in July. Particular instances, however, of extreme cold and heat have been observed. In January 1795, the mercury in Fahrenheit's thermometer sunk to 38 degrees below the freezing point, and in July 1808, rose to 94 degrees in the shade.

One of my favorite sources of historical information is the tourist guidebook. The following excerpt is from the 1827 edition of Leigh's new picture of London: or A view of the political, religious, medical, literary, municipal, commercial, and moral state of the British metropolis.

~~~~~

All the streets of London are paved with great regularity, and have a foot-path, laid with flags, divided from the carriage-way: the latter is formed by small square blocks of Scotch granite. The foot-path has a regular curb stone, raised some inches above the carriage-way; of course the accommodation to the foot passenger must depend upon the breadth of the avenue: but as every alteration for many years past, has tended to widen the streets and lanes of the metropolis, the narrow avenues which admit carriages are gradually increasing in convenience to the pedestrian. In 1823, a new method of forming the carriage-ways of London was commenced in St. James's Square, under the superintendence of Mr. McAdam. By this process, which consists of breaking the stones into small pieces of the same size, it is hoped that a more level road will be obtained than the old pavement. Nearly all the streets are lighted by gas, an improvement which has only been introduced within a few years.

The Climate of London is temperate, but variable and inclined to moisture. The average temperature is 51° 9', although it varies from 20° to 81° the greatest cold usually occurring in January, and the greatest heat in July. Particular instances, however, of extreme cold and heat have been observed. In January 1795, the mercury in Fahrenheit's thermometer sunk to 38 degrees below the freezing point, and in July 1808, rose to 94 degrees in the shade.

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Silver Tureens & Crowns for Queens

Susan reporting:

Earlier this summer we marveled at a golden soup tureen from 18th c. France. It seems only fair that we show you how the English aristocracy had their soup brought to table.

This gorgeous tureen and stand was made of silver – a great deal of silver, for it's a very large tureen – around 1824. Wealthy Englishmen of the period liked a glittering display of silver on their dining table, and vied with one another for the biggest, most ornate candlesticks, centerpieces, and serving dishes. The tureen is almost alive with marine motifs, including dolphins, lobsters, and shells, a mermaid on one side and merman on the other. While this would make it perfect for serving lobster bisque, more likely the designs would have been considered patriotic for an island nation that was justly proud of its navy.

The tureen was made for Fletcher Norton, 3rd Baron Grantley (1796-1875). A veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, Lord Grantley never married, but if this tureen was any indication, he set a lavish bachelor table. He also must have believed in patronizing the best silversmiths in London. This masterpiece is the work of Robert Garrard, Jr., of Garrard & Company, whose family's shop in Panton Street catered to the highest ranks of fashionable society, including the Royal Princes. Twenty years after this tureen was made, the young Queen Victoria appointed Garrard & Company as the Crown Jewelers – which in turn must have made the baron value his fabulous tureen even more.

Above: Silver tureen and stand made by Robert Garrard, Jr., London, England, 1824-25. Winterthur Museum

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

Dressing a character in 1831

Loretta reports:

Throughout Last Night’s Scandal, comments are made regarding fashionable dress in 1831. The heroine herself speaks of the styles with some exasperation. In case you were wondering, here’s the sort of thing she might have worn. I'm obliged to use fashions for November 1831, because La Belle Assemblée offered no fashion prints for October, apparently because they used the space for illustrations of King William IV’s coronation. More from the November fashions will will appear at my other blog. You may find it interesting to compare & contrast English and French fashions.

ENGLISH FASHIONS

CARRIAGE DRESS.

A DRESS of white chaly, finished round the back part of the corsage, which is of a three-quarter height, with a triple fold disposed en pelerine, and descending on each side of the front in the form of an X; immediately above this trimming a light bouquet is embroidered in the centre of the bosom, in pearl-grey silk. The sleeves are of the gigot shape, embroidered at the hand in pearl-grey silk. A Grecian border is worked in light waves above the hem, and bouquets issue from it at regular distances. The pelisse worn over this dress is of pearl-grey gros de Tours. The corsage, made up to the throat, but without a collar, has a slight fulness at the bottom of the waist, before and behind. The pelerine is of moderate size, and very open on the bosom: it is trimmed with a satin rouleau, to correspond, placed at some distance from the edge. The sleeves are of the gigot shape, and of the usual size. The pelisse is open in front, and a little rounded before in the tunic style. It is trimmed down the fronts, and round the border, with a satin rouleau. Collerette fichu of white tulle, trimmed with the same material, and sustained round the throat by a neck-knot of straw-coloured gauze ribbon. The manchettes are also of tulle. The hat is of straw-coloured gros des Indes; a round crown of moderate height: the brim, deeper and wider than they have lately been worn, is trimmed on the inside with light bows of rich white gauze ribbon; a band of ribbon crosses the crown, and a profusion of bows are placed in front.

CARRIAGE BONNET.

IT is composed of green satin ; the shade is that called vert des Indes ; it is of the capôte shape, but the brim is somewhat larger than usual, and is lined with white satin, upon which blond lace is arranged en evantail. The crown is trimmed with sprigs of foliage, composed of a mixture of satin and gros des Indes, and intermixed with ears of ripe corn, of the natural colour. The curtain at the back of the crown is formed by a wreath of leaves. The mentonnières are of blond lace.

From La Belle assemblée: or, Court and fashionable magazine; containing interesting and original literature, and records of the beau-monde. 1831

Throughout Last Night’s Scandal, comments are made regarding fashionable dress in 1831. The heroine herself speaks of the styles with some exasperation. In case you were wondering, here’s the sort of thing she might have worn. I'm obliged to use fashions for November 1831, because La Belle Assemblée offered no fashion prints for October, apparently because they used the space for illustrations of King William IV’s coronation. More from the November fashions will will appear at my other blog. You may find it interesting to compare & contrast English and French fashions.

ENGLISH FASHIONS

CARRIAGE DRESS.

A DRESS of white chaly, finished round the back part of the corsage, which is of a three-quarter height, with a triple fold disposed en pelerine, and descending on each side of the front in the form of an X; immediately above this trimming a light bouquet is embroidered in the centre of the bosom, in pearl-grey silk. The sleeves are of the gigot shape, embroidered at the hand in pearl-grey silk. A Grecian border is worked in light waves above the hem, and bouquets issue from it at regular distances. The pelisse worn over this dress is of pearl-grey gros de Tours. The corsage, made up to the throat, but without a collar, has a slight fulness at the bottom of the waist, before and behind. The pelerine is of moderate size, and very open on the bosom: it is trimmed with a satin rouleau, to correspond, placed at some distance from the edge. The sleeves are of the gigot shape, and of the usual size. The pelisse is open in front, and a little rounded before in the tunic style. It is trimmed down the fronts, and round the border, with a satin rouleau. Collerette fichu of white tulle, trimmed with the same material, and sustained round the throat by a neck-knot of straw-coloured gauze ribbon. The manchettes are also of tulle. The hat is of straw-coloured gros des Indes; a round crown of moderate height: the brim, deeper and wider than they have lately been worn, is trimmed on the inside with light bows of rich white gauze ribbon; a band of ribbon crosses the crown, and a profusion of bows are placed in front.

CARRIAGE BONNET.

IT is composed of green satin ; the shade is that called vert des Indes ; it is of the capôte shape, but the brim is somewhat larger than usual, and is lined with white satin, upon which blond lace is arranged en evantail. The crown is trimmed with sprigs of foliage, composed of a mixture of satin and gros des Indes, and intermixed with ears of ripe corn, of the natural colour. The curtain at the back of the crown is formed by a wreath of leaves. The mentonnières are of blond lace.

From La Belle assemblée: or, Court and fashionable magazine; containing interesting and original literature, and records of the beau-monde. 1831

Monday, August 16, 2010

Men & Women Swimming Together...in 1810

Susan reporting:

With summer winding down, I thought I'd post a print that's appropriate for the last days of August. It's going to be a case of "one picture is worth a thousand words", too, because I can find very little to share about its history.

Called "Les Nageurs" ("The Swimmers"), this image is No. 15 in a rare series of early 19th c. French prints called Caricatures Parisiennes: Le Supreme Bon Ton. The prints show the pastimes of fashionable young people in Napoleon's Paris. While they're called "caricatures", they have none of the bite of their English counterparts, and more of the hand-tinted elegance of fashion plates.

But consider what a racy scene this must have been at the time. Swimming had long been considered good manly exercise (recall Charles II, swimming in the Thames outside Whitehall in the 1660s) and ladies, too, had been known to dabble in the water, but I can't recall seeing any other picture from this early date showing the two parties in the water together. They're clearly swimming, too, not just splashing about. That one guy hopping into the water with his pointed toes is showing off his chiseled, beach-boy physique (as well as his woolly sideburns), hoping to be scouted for some long-distant episode of Jersey Shore.

Even more interesting is that they appear to be wearing stylish costumes designed specifically for the activity. No skinny-dipping for these folks! The men's drawers are based on breeches or drawers, with button-front falls (that flap-like fly) in the front, and the hems are trimmed with a natty contrasting border, much like the trunks worn by 1950s lifeguards. The ladies are a little harder to figure out, but they, too, seem to be wearing specific swimming "dress," with caps over their hair and knee-length, sleeveless garments. There are buttons under the arm that have become unbuttoned (?) and I'm guessing the fabric is linen by the revealing way it's clinging to the lady's body. For that matter, the men's drawers aren't hiding many secrets, either, which makes this co-ed swim party all the more extraordinary.

Was this kind of easy, athletic freedom common in Paris at the time? Or was it only an invention (or wishful thinking) by the artist?

Above: Les Nageurs (The Swimmers), from the series Le Supreme Bon Ton, No. 15; artist unknown; published by Martinet, Paris, c. 1810-1815

With summer winding down, I thought I'd post a print that's appropriate for the last days of August. It's going to be a case of "one picture is worth a thousand words", too, because I can find very little to share about its history.

Called "Les Nageurs" ("The Swimmers"), this image is No. 15 in a rare series of early 19th c. French prints called Caricatures Parisiennes: Le Supreme Bon Ton. The prints show the pastimes of fashionable young people in Napoleon's Paris. While they're called "caricatures", they have none of the bite of their English counterparts, and more of the hand-tinted elegance of fashion plates.

But consider what a racy scene this must have been at the time. Swimming had long been considered good manly exercise (recall Charles II, swimming in the Thames outside Whitehall in the 1660s) and ladies, too, had been known to dabble in the water, but I can't recall seeing any other picture from this early date showing the two parties in the water together. They're clearly swimming, too, not just splashing about. That one guy hopping into the water with his pointed toes is showing off his chiseled, beach-boy physique (as well as his woolly sideburns), hoping to be scouted for some long-distant episode of Jersey Shore.

Even more interesting is that they appear to be wearing stylish costumes designed specifically for the activity. No skinny-dipping for these folks! The men's drawers are based on breeches or drawers, with button-front falls (that flap-like fly) in the front, and the hems are trimmed with a natty contrasting border, much like the trunks worn by 1950s lifeguards. The ladies are a little harder to figure out, but they, too, seem to be wearing specific swimming "dress," with caps over their hair and knee-length, sleeveless garments. There are buttons under the arm that have become unbuttoned (?) and I'm guessing the fabric is linen by the revealing way it's clinging to the lady's body. For that matter, the men's drawers aren't hiding many secrets, either, which makes this co-ed swim party all the more extraordinary.

Was this kind of easy, athletic freedom common in Paris at the time? Or was it only an invention (or wishful thinking) by the artist?

Above: Les Nageurs (The Swimmers), from the series Le Supreme Bon Ton, No. 15; artist unknown; published by Martinet, Paris, c. 1810-1815

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Intrepid Women: Julia Child's Kitchen

Loretta reports:

Celebrity chefs are nothing new. The Regency era had Marie-Antoine Carême, who cooked for emperors and kings. But he worked in vast palace kitchens, with an army of helpers, preparing extravagant meals for hundreds of people at a time.

Julia Child worked, so far as we could see, in her own kitchen, and in the era before the Food Channel and 24/7 shows featuring celebrity chefs and wannabe celebrity chefs, she brought to American viewers her own unforgettable way with cooking. While perhaps not as glamorous as Carême’s, her story is at least as exciting. Maybe working for the OSS during WWII gave her the wherewithal to take on France’s male cooking establishment, or maybe she was just born that way. But I figure it took some nerve for a woman—and an American—to try to succeed at Le Cordon Bleu cooking school in the 1940s. I guess it helps to be six foot two, towering over all those Frenchmen who are certain you Don’t Belong Here and probably wish you would go away. But one must have guts, too, (those knives are very big and very sharp) and a certain strength of character and an optimistic spirit. Whatever it took, she got her diploma, and went on to write a cookbook still considered a classic, and to host her famous and much-loved cooking show.

The movie Julie and Julia, wherein Meryl Streep and Stanley Tucci shone as Julia and Paul Child, reminded me what a delight she was. So, when I found myself in Washington, D.C., some weeks ago, I went straight to the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, to see Julia Child’s Kitchen. This wasn’t the only item of interest there, but it was Number One on my list.

Here's the diploma and one view of the kitchen. I'll put up additional photos at my other blog.

Celebrity chefs are nothing new. The Regency era had Marie-Antoine Carême, who cooked for emperors and kings. But he worked in vast palace kitchens, with an army of helpers, preparing extravagant meals for hundreds of people at a time.

Julia Child worked, so far as we could see, in her own kitchen, and in the era before the Food Channel and 24/7 shows featuring celebrity chefs and wannabe celebrity chefs, she brought to American viewers her own unforgettable way with cooking. While perhaps not as glamorous as Carême’s, her story is at least as exciting. Maybe working for the OSS during WWII gave her the wherewithal to take on France’s male cooking establishment, or maybe she was just born that way. But I figure it took some nerve for a woman—and an American—to try to succeed at Le Cordon Bleu cooking school in the 1940s. I guess it helps to be six foot two, towering over all those Frenchmen who are certain you Don’t Belong Here and probably wish you would go away. But one must have guts, too, (those knives are very big and very sharp) and a certain strength of character and an optimistic spirit. Whatever it took, she got her diploma, and went on to write a cookbook still considered a classic, and to host her famous and much-loved cooking show.

The movie Julie and Julia, wherein Meryl Streep and Stanley Tucci shone as Julia and Paul Child, reminded me what a delight she was. So, when I found myself in Washington, D.C., some weeks ago, I went straight to the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History, to see Julia Child’s Kitchen. This wasn’t the only item of interest there, but it was Number One on my list.

Here's the diploma and one view of the kitchen. I'll put up additional photos at my other blog.

Saturday, August 14, 2010

Scarlett's Curtain Dress Meets Carol Burnett (Silly Video Extraordinaire)

Susan reporting:

It IS the weekend, our time for silly history videos, and this has to be one of the silliest videos of all time. Originally broadcast in 1976 as part of The Carol Burnett Show, this lengthy (it's in two parts) spoof of Gone With the Wind is called Went With the Wind. Without requiring a Spoiler Alert, I will say that Scarlett's famous Curtain Dress plays an important role in Burnett's, ah, interpretation. And here's real proof that each version has achieved its place in American popular history: both have been immortalized as Barbie dolls.

Many thanks to Marilyn Watson for tracking down the Carol Burnett sketch on YouTube.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

Dressing History for the Movies: Scarlett's Curtain Dress

Susan reporting:

Historic clothing is fragile. Never intended to last forever, examples of clothing from the past can perish from poor storage, well-intended but disastrous wear for fancy dress, or a long-ago owner's perspiration. Even the garment's own dye or ornament over time can cause the fabric to disintegrate. Here's an excellent blog on the perils that face historic clothing, including several heart-breaking examples, from the Museum of the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in Los Angeles.

Sadly the appeals to contribute to save this or that famous garment are never-ending. Restoration and climate-controlled storage are expensive, and the non-profit collections for historic dress are always in need of funding. But when this particular appeal appeared in my email this morning, I definitely took notice. Sometimes the most iconic historical garments don't even date from the period they represent, and such is the case of the famous green "Curtain Dress", left, worn by Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara in the 1939 movie Gone with the Wind.

As anyone who has seen the movie knows, the curtain dress is much more than an attractive costume. Sewn from her mother's velvet curtains and worn to seek money from Rhett Butler, the dress represents Scarlett's resourcefulness and determination as well as her sense of style, and is probably the single costume most remembered from the film. Great care was taken with its creation, and like all of Scarlett's costumes, it was closely based on historical examples from the 1860s (such as this fashion print, right.) It's even a accurate color of toxic green that was popular in interior decor as well as fashion. Here's the link to the costume's complete story, plus information about other GWTW costumes.

Unlike most movie costumes, however, the curtain dress and others from GWTW had a life of their own after the movie's release. Over the years, they were often sent out on tour to museums and special showings of the movie, to the point that the originals were finally recreated, and the replicas sent out on the road in their stead. Now the originals are kept at the University of Texas, who has sent out the appeal for their preservation. If you're interested, here's the link.

Many thanks to Michael Robinson for suggesting this blog.

Historic clothing is fragile. Never intended to last forever, examples of clothing from the past can perish from poor storage, well-intended but disastrous wear for fancy dress, or a long-ago owner's perspiration. Even the garment's own dye or ornament over time can cause the fabric to disintegrate. Here's an excellent blog on the perils that face historic clothing, including several heart-breaking examples, from the Museum of the Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising in Los Angeles.

Sadly the appeals to contribute to save this or that famous garment are never-ending. Restoration and climate-controlled storage are expensive, and the non-profit collections for historic dress are always in need of funding. But when this particular appeal appeared in my email this morning, I definitely took notice. Sometimes the most iconic historical garments don't even date from the period they represent, and such is the case of the famous green "Curtain Dress", left, worn by Vivian Leigh as Scarlett O'Hara in the 1939 movie Gone with the Wind.

As anyone who has seen the movie knows, the curtain dress is much more than an attractive costume. Sewn from her mother's velvet curtains and worn to seek money from Rhett Butler, the dress represents Scarlett's resourcefulness and determination as well as her sense of style, and is probably the single costume most remembered from the film. Great care was taken with its creation, and like all of Scarlett's costumes, it was closely based on historical examples from the 1860s (such as this fashion print, right.) It's even a accurate color of toxic green that was popular in interior decor as well as fashion. Here's the link to the costume's complete story, plus information about other GWTW costumes.

Unlike most movie costumes, however, the curtain dress and others from GWTW had a life of their own after the movie's release. Over the years, they were often sent out on tour to museums and special showings of the movie, to the point that the originals were finally recreated, and the replicas sent out on the road in their stead. Now the originals are kept at the University of Texas, who has sent out the appeal for their preservation. If you're interested, here's the link.

Many thanks to Michael Robinson for suggesting this blog.

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

A 17th Century Treasure Chest

Loretta reports:

Continuing the Illustrated Edition of Last Night’s Scandal…

A reader asked about the “German chest” my heroine tackles in the course of the story.

The Victorians, who had a tendency to…um…make stuff up, called these devices Armada Chests, and claimed that they were “treasure chests” from the Spanish Armada. They weren't. They were not from the Tudor period, but later—17th-18th C, and were mostly German-made.

My explorations turned up lots of images of these chests, still called Armada chests, and most usually for sale by antique dealers.

Non-copyright illustrations are hard to find, but this Google search will show you many examples—along with some completely irrelevant pictures.

The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art describes chests and strongboxes “fashioned from iron. Outstanding examples include the Armada Chest made in Nuremberg in the 17th century…a form of early safe." You can read the full entry here.

I came upon the phenomenon by accident—or serendipity—when I was looking for a chest to use in my story. A search for an "iron-bound chest" brought me to this this delightful inquiry at oldlocks.com.

I loved the complicated mechanism, the several keys, etc. Until this point, I’d no idea such things had existed. Those of you familiar with my characters will understand how perfect this was for my purposes.

The photograph above was taken at West Gate Towers and Museum, St Peter's Street, Canterbury, Kent by Linda Spashett (Storye book). Clicking on the link will bring you to its page on Wikimedia Commons, where you can enlarge the photo for a closer look.

Continuing the Illustrated Edition of Last Night’s Scandal…

A reader asked about the “German chest” my heroine tackles in the course of the story.

The Victorians, who had a tendency to…um…make stuff up, called these devices Armada Chests, and claimed that they were “treasure chests” from the Spanish Armada. They weren't. They were not from the Tudor period, but later—17th-18th C, and were mostly German-made.

My explorations turned up lots of images of these chests, still called Armada chests, and most usually for sale by antique dealers.

Non-copyright illustrations are hard to find, but this Google search will show you many examples—along with some completely irrelevant pictures.

The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art describes chests and strongboxes “fashioned from iron. Outstanding examples include the Armada Chest made in Nuremberg in the 17th century…a form of early safe." You can read the full entry here.

I came upon the phenomenon by accident—or serendipity—when I was looking for a chest to use in my story. A search for an "iron-bound chest" brought me to this this delightful inquiry at oldlocks.com.

I loved the complicated mechanism, the several keys, etc. Until this point, I’d no idea such things had existed. Those of you familiar with my characters will understand how perfect this was for my purposes.

The photograph above was taken at West Gate Towers and Museum, St Peter's Street, Canterbury, Kent by Linda Spashett (Storye book). Clicking on the link will bring you to its page on Wikimedia Commons, where you can enlarge the photo for a closer look.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Men Behaving Badly: Gentlemen Gamesters in 18th c. London

Susan reporting:

There have been gamblers as long as there have been two men with something to wager on and something to wager with. In 18th c. London, however, gaming was a ruinous epidemic. Gentlemen from the highest levels of English society played with a ruinous, reckless fury that shocked foreigners.

Even Horace Walpole (not exactly a wild rake) knew of young gentlemen who thought nothing of losing fifteen thousand pounds at the tables of private clubs; at Brooks's, he wrote in 1774,"a thousand meadows and cornfields are staked at every throw, and as many villages lost as in the earthquake that overwhelmed Herculaneum and Pompeii." Typical of the excess was young Charles James Fox, grandson of the Duke of Richmond and great-great grandson of Charles II, who had amassed gaming debts of over £140,000 before his twenty-fourth birthday – and this was in a time when an English family of the middling sort could live comfortably on £50 a year!

Here's a droll description of fashionable London gamesters from a 1773 Virginian newspaper, written as an anthropological observation by a "Gentleman who has travelled through different Parts of the Globe":

"I met with a very strange Set of Men, who often sat round a Table the whole Night, and even till the Morning is well advanced; but there is no Cloth laid for them, nor is there any Thing to gratify the Appetite. The Thunder might rattle over their Heads, two Armies might engage beside them, Heaven itself might threaten an instant Chaos, without making them stir, or in the least disturbing them; for they are deaf and dumb. At Times, indeed, they are heard to utter inarticulate Sounds, which have no Connexion with each other, and very little Meaning; yet will they roll their Eyes at each other in the oddest Manner imaginable. Often have I looked at them with wonder....Sometimes they appear furious, as Bedlamites; sometimes serious and gloomy, as the infernal Judges; and sometimes gasping with all the Anguish of a Criminal, as he is led to the Place of Execution."

"Heavens (exclaimed the Friends of our Traveller) what can be the Object of these unhappy Wretches? Are they Servants of the Publick?"

"No," the Traveller said.

"Then they are in Search of the Philosopher's Stone?"

"No."

"Oh! Now we have it; they are sent thither in Order to repent of, and to atone for, their Crimes."

"No, you are much deceived, my Friends, as ever."

"Good God! then they must be Madmen. Deaf, dumb, and insensible! What in the Name of Wonder can employ them?"

"Why, only one thing," the Traveller said. "It is GAMING."

Above: A Rake's Progress: The Gaming House (detail) by William Hogarth, 1732-35, Sir John Soane's Museum

Monday, August 9, 2010

The Scottish Castle

Loretta reports:

Continuing the Illustrated Edition of Last Night’s Scandal…

We move on to Scotland, and Gorewood Castle. Some years ago, I spent a few days (and sleepless nights*) at a wonderful castle in Scotland, which has a very interesting history. Not just the history history—Mary Queen of Scots escaping from a high window, defying Cromwell and getting a big divot blown into one side of the castle, that sort of thing—but its history as a building. It turned out that a great deal had been written about this place, and better yet, there were tons of old illustrations and floor plans and descriptions of its state in approximately the time of my story.

The place was Borthwick Castle, and after the usual artistic adjustments to suit my purposes, I turned it into Castle Horrid.

One fabulous resource was The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland from the 12th to the 18th Century by David MacGibbon and Thomas Ross. You can read the entry here.

This site, at the Mary Queen of Scots page, has lots of terrific pictures, particularly of the interior. The photos are far more numerous and interesting than my own collection.

And of course there's Borthwick Castle's own site, which is both beautiful and informative.

In case you were wondering, we stayed in the Mary Queen of Scots room. And yes, the staff regaled us with *ghost stories, and no, I could not understand what they were saying.

Sunday, August 8, 2010

Waving the Flag with Your Bed Hangings

Susan reporting:

Today most of us don't choose to make political statements with our home decor. Perhaps on our chests by way of a t-shirt, yes, but generally our curtains, slipcovers, and pillow cases are safe from endorsing one party or cause over another.

Not so in the past. Printed textiles were the height of fashion 250 years ago.The large scale of the designs made them especially popular for upholstery, curtains, bed hangings and coverlets, but they were also used for fashionable ladies' day gowns.

Costly cotton fabrics printed with wooden blocks had long been imported from India, but by the end of the 18th c. textile merchants in England and France had begun producing them as well, with thousands of craftsmen employed in the trade to meet the demand. Few of these designs were original artwork. Most were adapted from existing prints and paintings. Especially popular were landscapes, vignettes of country frolics, Oriental fantasies, and scenes from classical mythology. The designs were printed in a single color, usually on white or off-white cotton, with repeating motifs.

Soon political prints began to be incorporated into the English designs as well. Not only did the royal family appear, but also commemorations of famous historical events and battles. The textile merchants were quick to answer whatever demand the market might make – even if that market lay on the other side of the Atlantic.

In 1785, when this particular length of fabric, above, was printed, the American Revolution was still a very recent memory, and quite a sore one at that in England. But the victorious Americans were eager to display their newly minted patriotism, and venerating their first president and general George Washington was one of the most popular ways to do it. Thus the English textile merchants put aside their own politics and produced printed cottons like this one, with George as the victor crowned with laurels by a trumpeting angel, and well-attended by Liberty, cherubs, clouds of incense, eagles, and....flying ducks? Well, no matter. The Americans had their patriotic bed hangings (available in blue, black, and purple, as well as this red), and the English had their profit.

(A word about toile: this style of pattern is now often called toile, and turns up on everything from dinner plates to rain boots to lunch boxes. In the 18th c., however, toile referred to fabric that came from a specific French factory, the Manufacture Royale de Jouy, in the small town of Jouy-en-Josas near Versailles. With the sponsorship of the king, the factory was intended to replace the imported Indian cotton with cloth produced by French workers. The printed fabric produced there was called toile de Jouy: cloth of Jouy. Click here for some beautiful examples.)

Above: America Presenting at the Altar of Liberty Medallions of Her Illustrious Sons

Textile panel: plate print, printed in England; about 1785

Winterthur Museum

Today most of us don't choose to make political statements with our home decor. Perhaps on our chests by way of a t-shirt, yes, but generally our curtains, slipcovers, and pillow cases are safe from endorsing one party or cause over another.

Not so in the past. Printed textiles were the height of fashion 250 years ago.The large scale of the designs made them especially popular for upholstery, curtains, bed hangings and coverlets, but they were also used for fashionable ladies' day gowns.

Costly cotton fabrics printed with wooden blocks had long been imported from India, but by the end of the 18th c. textile merchants in England and France had begun producing them as well, with thousands of craftsmen employed in the trade to meet the demand. Few of these designs were original artwork. Most were adapted from existing prints and paintings. Especially popular were landscapes, vignettes of country frolics, Oriental fantasies, and scenes from classical mythology. The designs were printed in a single color, usually on white or off-white cotton, with repeating motifs.

Soon political prints began to be incorporated into the English designs as well. Not only did the royal family appear, but also commemorations of famous historical events and battles. The textile merchants were quick to answer whatever demand the market might make – even if that market lay on the other side of the Atlantic.

In 1785, when this particular length of fabric, above, was printed, the American Revolution was still a very recent memory, and quite a sore one at that in England. But the victorious Americans were eager to display their newly minted patriotism, and venerating their first president and general George Washington was one of the most popular ways to do it. Thus the English textile merchants put aside their own politics and produced printed cottons like this one, with George as the victor crowned with laurels by a trumpeting angel, and well-attended by Liberty, cherubs, clouds of incense, eagles, and....flying ducks? Well, no matter. The Americans had their patriotic bed hangings (available in blue, black, and purple, as well as this red), and the English had their profit.

(A word about toile: this style of pattern is now often called toile, and turns up on everything from dinner plates to rain boots to lunch boxes. In the 18th c., however, toile referred to fabric that came from a specific French factory, the Manufacture Royale de Jouy, in the small town of Jouy-en-Josas near Versailles. With the sponsorship of the king, the factory was intended to replace the imported Indian cotton with cloth produced by French workers. The printed fabric produced there was called toile de Jouy: cloth of Jouy. Click here for some beautiful examples.)

Above: America Presenting at the Altar of Liberty Medallions of Her Illustrious Sons

Textile panel: plate print, printed in England; about 1785

Winterthur Museum

Saturday, August 7, 2010

Shameless Self-Promotion: Loretta's a Bestseller!

Susan reporting:

This isn't so much Shameless Self-Promotion as it is Joyful Announcement: Loretta's new book, Last Night's Scandal, made a great cannonball of a splash in its first week of release, claiming spots on THREE bestseller lists: USAToday, Borders Books, and – duh-duh! – The New York Times.

Congratulations, Loretta!

Thursday, August 5, 2010

A walk to the York minster

Loretta reports:

We continue with Lisle & Olivia on their journey north, in Last Night’s Scandal.

Today’s stop is in York. A few years before my characters’ visit, The York Minister, the Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of St Peter, had been set on fire. Lisle & Olivia arrive at a time when the rebuilding was not yet under way.

The following excerpt is from The Cathedral Church of York: a description of its fabric

and a brief history of the archi-episcopal see, by A. Clutton-Brock. 1899

~~~~~