Susan reporting:

While Loretta and I spent a lot (a LOT) of time in museums, there are still things that, even at our absolute nerdiest, can stop us cold.

Hair pieces, false hair, and wigs have been in and out of style all the way back to ancient times, but I'd never seen anything quite like this. The museum placard calls it a "hair cap," and dates it to 1830-40. (To me the style looked a bit earlier – though that could be because the cap is probably American-made, and not from a fashion capitol like Paris or London.) Instead of costly human hair, it's made of dark brown silk, elaborately knotted and looped and twisted to simulate curls, waves, and braids.

Such a cap was worn over a lady's real hair, and was designed to boost what Nature had failed to provide. Fashions of the times emphasised the hair that framed the face, with the back of the head hidden beneath a lace-trimmed linen cap, and often a hat on top of that. This hair cap could have given the impression of an elegantly waved hairline, complete with a tidy bunch of curls over the ears.

But according to the placard, there were other advantages to a hair cap, too: "When running water was not available in homes, it was difficult to keep hair clean and styled. One advertisement suggests that caps like this one were especially convenient while traveling, when sanitary conditions were even less certain."

Hair cap, silk, 1830-40, Winterthur Museum.

Friday, July 30, 2010

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

On the (coaching) road again

Loretta reports:

Since a large section of Last Night’s Scandal is a “road book,” you might want to follow the journey using the same guide Olivia does. Paterson’s Roads lists the coaching roads, distances, and towns en route.

It marks the main coaching stops and the turnpike/toll gates as well as including descriptions of notable houses and sights along the way. It’s fascinating (at least to Nerdy History Girls & Boys), but not easy to follow.

What with alternative routes and cross roads, etc., not to mention changes in Royal Mail routes, it wanted a lot of thumbing back and forth to plot out the route from London to Edinburgh at the time of my story. Then I had to time the journey by coordinating with info from another book, because Paterson’s doesn’t list the mail coach arrival and departure times. I used the Royal Mail schedule as a rough way of calculating how long it would take Olivia’s carriage to get from one place to the next, depending on how much of a hurry she was in. I ended up making a spreadsheet to keep things straight.

(You will easily imagine my feelings when a copy editor questioned my timing, and thought my characters ought to be traveling at the pace of 50 years earlier (!!!!)—long before the roads were macadamized. But I digress, as Authors often will when the subject of copy edits arises.)

Here’s St. Leonard’s, aka the Shoreditch Church, from which the distance from London was measured. Getting out of London in those days was very much like getting out of any large city today. The difference was, one hadn’t as far to go. The urban sprawl hadn’t yet sprawled even as far as the Regent’s Canal. At right is an early map of the tollgates around town.

The first Road Incident occurs at the Falcon Inn, in Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/places/places-w/waltham-cross.htm (lots of interesting pictures at this site).

If you want to do more sightseeing with the characters, watch this space and Loretta Chase In Other Words in coming days.

Since a large section of Last Night’s Scandal is a “road book,” you might want to follow the journey using the same guide Olivia does. Paterson’s Roads lists the coaching roads, distances, and towns en route.

It marks the main coaching stops and the turnpike/toll gates as well as including descriptions of notable houses and sights along the way. It’s fascinating (at least to Nerdy History Girls & Boys), but not easy to follow.

What with alternative routes and cross roads, etc., not to mention changes in Royal Mail routes, it wanted a lot of thumbing back and forth to plot out the route from London to Edinburgh at the time of my story. Then I had to time the journey by coordinating with info from another book, because Paterson’s doesn’t list the mail coach arrival and departure times. I used the Royal Mail schedule as a rough way of calculating how long it would take Olivia’s carriage to get from one place to the next, depending on how much of a hurry she was in. I ended up making a spreadsheet to keep things straight.

(You will easily imagine my feelings when a copy editor questioned my timing, and thought my characters ought to be traveling at the pace of 50 years earlier (!!!!)—long before the roads were macadamized. But I digress, as Authors often will when the subject of copy edits arises.)

Here’s St. Leonard’s, aka the Shoreditch Church, from which the distance from London was measured. Getting out of London in those days was very much like getting out of any large city today. The difference was, one hadn’t as far to go. The urban sprawl hadn’t yet sprawled even as far as the Regent’s Canal. At right is an early map of the tollgates around town.

The first Road Incident occurs at the Falcon Inn, in Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/places/places-w/waltham-cross.htm (lots of interesting pictures at this site).

If you want to do more sightseeing with the characters, watch this space and Loretta Chase In Other Words in coming days.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Salad Days of 1699 with John Evelyn

Susan reporting:

When we think of dining in late 17th c. England (if, admittedly, we think of it at all), it's the roaring display of roasted beef and venison and pheasant, turtle soup and eel pie. The England of Charles II seems such a time of wine, women, and song, that it's hard to imagine a menu that included...salad.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) was a serious, scholarly gentleman, a public servant, writer, philosopher, and horticulturalist whose agile mind wandered from the study of architecture to gardens, from paintings to the pollution of London. He was a founding member of the Royal Society, and also a friend of Charles II. In a court full of carnivores, Evelyn was a confirmed vegetarian, believing that the key to health was to be found in the garden, not on the hunt. The fact that Evelyn lived to be eighty-six, while the king died shy of his fifty-fifth birthday, might be considered proof enough.

Evelyn was so devoted to his beliefs that he wrote an entire book on the subject: Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets. Published in 1699, the book suggested what kinds of plants and herbs to include in a salad garden, their cultivation, and recipes. To Evelyn, raw salads were more fit for masculine tastes, while he recommended that vegetables be "Boil'd, Bak'd, Pickl'd, or otherwise disguis'd, variously accommodated by skillful Cooks, to render them grateful to the more feminine Palat."

On the whole, though, his advice seems remarkably contemporary. Here's how he prepared greens:

Preparatory to the Dressing therefore, let your Herby Ingredients be exquisitely cull'd, and cleans'd of all worm-eaten, slimy, cander'd, dry, spotted, or any way vitiated Leaves. And then that they be rather discretely sprinkl'd, than over-much sob'd with Spring-Water, especially Lettuce....After washing, let them remain a while in the Cullender, to drain the superfluous moisture; And lastly, swing them together gently in a clean course Napkin; and so they will be in perfect condition to receive the Intinctus following.

The "Intinctus" is a dressing of "the Yolks of fresh and new-laid Eggs, boil'd moderately hard, to be mingl'd and mash'd with the Mustard, Olive Oyl, and Vinegar; and cut into quarters, and eat with the Herbs." Sounds mighty tasty!

Like to try this and other recipes from John Evelyn? Acetaria is available as a thoroughly modern free ebook download here. With all of John Evelyn's interests, it's very easy to imagine him sitting beneath the trees in his garden with an iPad in hand....

Above: An 18th century kitchen garden in Colonial Williamsburg

Below: John Evelyn, by Sir Godrey Kneller, 1687

When we think of dining in late 17th c. England (if, admittedly, we think of it at all), it's the roaring display of roasted beef and venison and pheasant, turtle soup and eel pie. The England of Charles II seems such a time of wine, women, and song, that it's hard to imagine a menu that included...salad.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) was a serious, scholarly gentleman, a public servant, writer, philosopher, and horticulturalist whose agile mind wandered from the study of architecture to gardens, from paintings to the pollution of London. He was a founding member of the Royal Society, and also a friend of Charles II. In a court full of carnivores, Evelyn was a confirmed vegetarian, believing that the key to health was to be found in the garden, not on the hunt. The fact that Evelyn lived to be eighty-six, while the king died shy of his fifty-fifth birthday, might be considered proof enough.

Evelyn was so devoted to his beliefs that he wrote an entire book on the subject: Acetaria: A Discourse of Sallets. Published in 1699, the book suggested what kinds of plants and herbs to include in a salad garden, their cultivation, and recipes. To Evelyn, raw salads were more fit for masculine tastes, while he recommended that vegetables be "Boil'd, Bak'd, Pickl'd, or otherwise disguis'd, variously accommodated by skillful Cooks, to render them grateful to the more feminine Palat."

On the whole, though, his advice seems remarkably contemporary. Here's how he prepared greens:

Preparatory to the Dressing therefore, let your Herby Ingredients be exquisitely cull'd, and cleans'd of all worm-eaten, slimy, cander'd, dry, spotted, or any way vitiated Leaves. And then that they be rather discretely sprinkl'd, than over-much sob'd with Spring-Water, especially Lettuce....After washing, let them remain a while in the Cullender, to drain the superfluous moisture; And lastly, swing them together gently in a clean course Napkin; and so they will be in perfect condition to receive the Intinctus following.

The "Intinctus" is a dressing of "the Yolks of fresh and new-laid Eggs, boil'd moderately hard, to be mingl'd and mash'd with the Mustard, Olive Oyl, and Vinegar; and cut into quarters, and eat with the Herbs." Sounds mighty tasty!

Like to try this and other recipes from John Evelyn? Acetaria is available as a thoroughly modern free ebook download here. With all of John Evelyn's interests, it's very easy to imagine him sitting beneath the trees in his garden with an iPad in hand....

Above: An 18th century kitchen garden in Colonial Williamsburg

Below: John Evelyn, by Sir Godrey Kneller, 1687

Monday, July 26, 2010

A stop at Somerset House

Loretta reports:

There’s the lady with the drum again. Yes, it’s Shameless Self-Promotion time. My new book, Last Night’s Scandal, is out now! That means you can expect to see blogs here and at Loretta Chase In Other Words presenting the kind of Nerdy History Girl background that doesn’t get into the novels. Plus pictures!

Today we’re taking a look at Somerset House, where Lisle gives a lecture to the Society of Antiquaries. Since they most inconveniently had their normal meetings between “November until the end of Trinity Term,”* and my story starts in October, I took artistic liberties, and created a special meeting, with, I trust, a reasonable explanation.

The first view is from The Microcosm of London. You can read the text about the building here.

This view is a little early—the Microcosm was published between 1808 and 1810—but the exterior is still recognizable, as this photo illustrates.

Outside, on the Strand, an Olivia-generated Incident occurs. The next illustration shows the general area of the Incident a few years after the time of the story—but it’s near enough for our purposes, and was the view I had in mind when I wrote the scene.

*Mary Cathcart Borer, An Illustrated Guide to London 1800.

There’s the lady with the drum again. Yes, it’s Shameless Self-Promotion time. My new book, Last Night’s Scandal, is out now! That means you can expect to see blogs here and at Loretta Chase In Other Words presenting the kind of Nerdy History Girl background that doesn’t get into the novels. Plus pictures!

Today we’re taking a look at Somerset House, where Lisle gives a lecture to the Society of Antiquaries. Since they most inconveniently had their normal meetings between “November until the end of Trinity Term,”* and my story starts in October, I took artistic liberties, and created a special meeting, with, I trust, a reasonable explanation.

The first view is from The Microcosm of London. You can read the text about the building here.

This view is a little early—the Microcosm was published between 1808 and 1810—but the exterior is still recognizable, as this photo illustrates.

Outside, on the Strand, an Olivia-generated Incident occurs. The next illustration shows the general area of the Incident a few years after the time of the story—but it’s near enough for our purposes, and was the view I had in mind when I wrote the scene.

*Mary Cathcart Borer, An Illustrated Guide to London 1800.

Sunday, July 25, 2010

The Regent of THE Regency (the silly video version of the life of George IV)

Susan reporting:

It's such a horribly hot weekend in most of America (ah, July) that it seems only fitting that we post another of our favorite Horrible Histories videos.

This one follows the career and reign of King George IV (1762-1830), a king who is more famous for being a regent than a ruler in his own right, serving as prince regent while his father George III suffered through bouts of madness. George IV was better known for his extravagant lifestyle, prodigious appetite, and many mistresses than for any genuine leadership, and even the beautiful palaces (like the Royal Pavilion at Brighton) that he commissioned were viewed at the time as only more examples of his spendthrift's excess.

Understandably George received little respect from his subjects. The Times famously noted at his death that "there never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures than this deceased king. What eye has wept for him? What heart has heaved one throb of unmercenary sorrow?... If he ever had a friend, a devoted friend from any rank of life, we protest that the name of him or her never reached us."

In comparison to that, the Horrible Histories treatment of his life is downright respectful.

Right: George IV, King of Great Britain, by John Russell, 1790-92

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Men Behaving Boldly: William Penn & Charles II

Susan reports:

Here in Pennsylvania where I live, William Penn (1644-1718) is a venerable figure. As the founder of the state, he is usually portrayed as a Quaker elder, wise, peace-loving, considerate, and just: everything a leader should be.

But that all came later, after 1682 and after he received the sizable grant of land that he would help colonize. The younger William Penn was the despair of his father, a career naval officer and administrator. To Admiral Penn, William was a rebellious idealist who stubbornly refused to take advantage of the family's connections at the court of the newly-crowned Charles II. Instead William chose to follow his own course, including becoming a member of the Society of Friends. The Friends – Quakers to the rest of the world – held many beliefs that infuriated the Admiral; most disturbing was the Friend's insistence that God had created all men equal, and that the concept of absolute monarchy (that kings had been determined directly by God) was rubbish. Friends did not curtsy or bow or remove their hats before their betters, because no one was better than anyone else. This was not only heresy to Anglican Englishmen like the Admiral, but also came perilously close to treason. Yet William was determined in his new faith, and refused to be shaken from it, eventually becoming one of its leaders.

Charles II, the king that William refused to acknowledge, was not a monarch who enjoyed public displays of conflict. Unlike many other rulers, Charles never indulged in petty tyranny or intemperate rages simply because he was king and everybody else wasn't. He saved his anger for important battles (like those with Parliament), and instead led his day-to-day life with mild and gentlemanly manners.

All of which makes the following, often-repeated story more fascinating. It may be apocryphal, but it rings so true to the characters of the two men that there must surely be more than a kernel of truth to it. This version comes by way of Royal Charles by Antonia Fraser.

by Antonia Fraser.

One day Charles entered a crowded chamber in Whitehall Palace. As was the custom, every lady curtsied and every gentleman bowed and removed his hat. Except for one: William Penn, the Admiral's embarrassing Quaker son. Determined to make his point for his faith, William remained upstanding, his hat firmly on his head.

Charles stopped before him, pointedly taking note of what could be considered treasonous defiance, and could, too, be rewarded with quick trip to the Tower.

Then the king slowly removed his own hat. This was not what anyone expected, including William himself.

"Friend Charles," William said, with even more daring. "Why dost thou not keep on thy hat?"

Unperturbed, the king answered. "Because it is the custom of this place that only one man should remain uncovered at a time."

Crisis averted!

Above: William Penn, copy of a portrait by Sir Peter Lely

Below: Charles II, by James Wright

Here in Pennsylvania where I live, William Penn (1644-1718) is a venerable figure. As the founder of the state, he is usually portrayed as a Quaker elder, wise, peace-loving, considerate, and just: everything a leader should be.

But that all came later, after 1682 and after he received the sizable grant of land that he would help colonize. The younger William Penn was the despair of his father, a career naval officer and administrator. To Admiral Penn, William was a rebellious idealist who stubbornly refused to take advantage of the family's connections at the court of the newly-crowned Charles II. Instead William chose to follow his own course, including becoming a member of the Society of Friends. The Friends – Quakers to the rest of the world – held many beliefs that infuriated the Admiral; most disturbing was the Friend's insistence that God had created all men equal, and that the concept of absolute monarchy (that kings had been determined directly by God) was rubbish. Friends did not curtsy or bow or remove their hats before their betters, because no one was better than anyone else. This was not only heresy to Anglican Englishmen like the Admiral, but also came perilously close to treason. Yet William was determined in his new faith, and refused to be shaken from it, eventually becoming one of its leaders.

Charles II, the king that William refused to acknowledge, was not a monarch who enjoyed public displays of conflict. Unlike many other rulers, Charles never indulged in petty tyranny or intemperate rages simply because he was king and everybody else wasn't. He saved his anger for important battles (like those with Parliament), and instead led his day-to-day life with mild and gentlemanly manners.

All of which makes the following, often-repeated story more fascinating. It may be apocryphal, but it rings so true to the characters of the two men that there must surely be more than a kernel of truth to it. This version comes by way of Royal Charles

One day Charles entered a crowded chamber in Whitehall Palace. As was the custom, every lady curtsied and every gentleman bowed and removed his hat. Except for one: William Penn, the Admiral's embarrassing Quaker son. Determined to make his point for his faith, William remained upstanding, his hat firmly on his head.

Charles stopped before him, pointedly taking note of what could be considered treasonous defiance, and could, too, be rewarded with quick trip to the Tower.

Then the king slowly removed his own hat. This was not what anyone expected, including William himself.

"Friend Charles," William said, with even more daring. "Why dost thou not keep on thy hat?"

Unperturbed, the king answered. "Because it is the custom of this place that only one man should remain uncovered at a time."

Crisis averted!

Above: William Penn, copy of a portrait by Sir Peter Lely

Below: Charles II, by James Wright

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Corset advertisement for 1807

Loretta reports:

Sometimes the advertisements from the times tell us more than the fashion plates and descriptions do. This one, from the July 1807 La Belle Assemblée, mentions some common complaints and viewpoints about health as well as fashion. It offers as well a glimpse into selling practices.

~~~~~

STAYS, BY HER MAJESTY'S STAY-MAKER.

The elastic cottoned long Stay invented by Mrs. HARMAN, who alone can make them in their genuine perfection.

These so much admired Stays obviate every objection complained of in Patent Stays, not being subject to the disagreeable necessity of lacing under the arm, or having knit gores, so very elastic as to be in effect no stay or support whatever. Mrs. Harman's Stays adapted to give the wearer the true Grecian form, must be seen to give Ladies an adequate idea of their beauty and utility, therefore Mrs. H. has various sizes ready to send for the inspection of those Ladies who live at a distance from London.

Stays, being in the present style of dress of great importance, Mrs. Harman recommends it to the serious consideration of Ladies what sort of Stays they wear; long Stays have now for a considerable time made part of the female costume, and have been variously made according to the knowledge, taste, or strength of invention in the maker, so have they, more or less pleased, but one general complaint has attended them, namely, that on some forms they would wrinkle on the hips, and prove uncomfortable in sitting; Mrs. Harman from a close observation and imitation of nature, has constructed a Stay which will not be attended with these inconveniencies, and at the same time will give an agreeable and graceful shape to the shoulders, reducing the bosom if too embonpoint, or increasing its natural appearance (if too diminutive) to the taste of the wearer, and as her cottoned Stays are exquisitely easy and pliant, they preserve to the slender form all its native roundness, while they guard from cold, the most susceptable parts of the body. Mrs. H. in availing herself of the Lectures of Statuaries and Medical men, on the subject of the female form, feels herself competent to say, that her Stays are the most perfect combination of study, talent, and attention to fashion and health that can be produced. Those Ladies living at a distance from London or Bath, applying by letter, (post paid) will be informed of the proper method to send their measure for Stays, No. 18, New Bond-street, London; or No. 6, Westgate Buildings. Bath. [564]

~~~~~

From La Belle assemblée, Volume 2

Publisher J. Bell, 1807

Sometimes the advertisements from the times tell us more than the fashion plates and descriptions do. This one, from the July 1807 La Belle Assemblée, mentions some common complaints and viewpoints about health as well as fashion. It offers as well a glimpse into selling practices.

~~~~~

STAYS, BY HER MAJESTY'S STAY-MAKER.

The elastic cottoned long Stay invented by Mrs. HARMAN, who alone can make them in their genuine perfection.

These so much admired Stays obviate every objection complained of in Patent Stays, not being subject to the disagreeable necessity of lacing under the arm, or having knit gores, so very elastic as to be in effect no stay or support whatever. Mrs. Harman's Stays adapted to give the wearer the true Grecian form, must be seen to give Ladies an adequate idea of their beauty and utility, therefore Mrs. H. has various sizes ready to send for the inspection of those Ladies who live at a distance from London.

Stays, being in the present style of dress of great importance, Mrs. Harman recommends it to the serious consideration of Ladies what sort of Stays they wear; long Stays have now for a considerable time made part of the female costume, and have been variously made according to the knowledge, taste, or strength of invention in the maker, so have they, more or less pleased, but one general complaint has attended them, namely, that on some forms they would wrinkle on the hips, and prove uncomfortable in sitting; Mrs. Harman from a close observation and imitation of nature, has constructed a Stay which will not be attended with these inconveniencies, and at the same time will give an agreeable and graceful shape to the shoulders, reducing the bosom if too embonpoint, or increasing its natural appearance (if too diminutive) to the taste of the wearer, and as her cottoned Stays are exquisitely easy and pliant, they preserve to the slender form all its native roundness, while they guard from cold, the most susceptable parts of the body. Mrs. H. in availing herself of the Lectures of Statuaries and Medical men, on the subject of the female form, feels herself competent to say, that her Stays are the most perfect combination of study, talent, and attention to fashion and health that can be produced. Those Ladies living at a distance from London or Bath, applying by letter, (post paid) will be informed of the proper method to send their measure for Stays, No. 18, New Bond-street, London; or No. 6, Westgate Buildings. Bath. [564]

~~~~~

From La Belle assemblée, Volume 2

Publisher J. Bell, 1807

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Notorious History: Jenny Diver, Pickpocket

Susan reports:

If you're familiar with John Gay's famous 18th c. ballad opera The Beggar's Opera, then you've heard of Jenny Diver. For his character, Gay borrowed the name of one of London's most infamous female pickpockets. Mary Young (1700?-1741) was an Irish seamstress who found thieving in London much more profitable than stitching in Dublin. Known by the name of Jenny Diver in honor of her dexterity at plucking purses, her ingenuity and daring soon made her a legend, and her exploits earned her a place in The Newgate Calendar. Here are two:

Jenny, accompanied by one of her female accomplices, joined the crowd at the entrance of a place of worship...where a popular divine was to preach, and, observing a young gentleman with a diamond ring on his finger, she held out her hand, which he kindly received in order to assist her: at this juncture she contrived to get possession of the ring without the knowledge of the owner; after which she slipped behind her companion....Upon his leaving the meeting [the gentleman] missed his ring, and mentioned his loss to the persons who were near him, adding that he suspected it to be stolen by a woman whom he had endeavoured to assist in the crowd; but, as the thief was unknown, she escaped....

[Soon after] this exploit, Jenny procured a pair of false hands and arms to be made, and concealed her real ones under her clothes; she then, putting something beneath her stays to make herself appear as if in a state of pregnancy, repaired on a Sunday evening to the place of worship above mentioned in a sedan chair, one of the gang going before to procure a seat among the genteeler part of the congregation, and another attending in the character of a footman. Jenny being seated between two elderly ladies, each of whom had a gold watch by her side, she conducted herself with great seeming devotion; but, the service being nearly concluded, she seized the opportunity, when the ladies were standing up, of stealing their watches, which she delivered to an accomplice in an adjoining pew. The devotions being ended, the congregation were preparing to depart, when the ladies discovered their loss, and a violent clamour ensued. One of the injured parties exclaimed "That her watch must have been taken either by the devil or the pregnant woman!" on which the other said, "She could vindicate the pregnant lady, whose hands she was sure had not been removed from her lap during the whole time of her being in the pew."

At last Jenny's luck ran out, and she was captured, tried, and hung at Tyburn in 1741. Yet even at her execution, her notoriety separated her from common thieves: instead of traveling the last journey to the gallows in an open cart, she was granted a lady's farewell, and made the trip in a coach.

Above: Detail from The Rake's Progress: The Rake at the Rose Tavern by William Hogarth, 1732.

Update: I'd intended to include the link to Jenny's complete entry in The Newgate Calendar for those who are interested. My apologies for forgetting - here it is: Jenny Diver.

If you're familiar with John Gay's famous 18th c. ballad opera The Beggar's Opera, then you've heard of Jenny Diver. For his character, Gay borrowed the name of one of London's most infamous female pickpockets. Mary Young (1700?-1741) was an Irish seamstress who found thieving in London much more profitable than stitching in Dublin. Known by the name of Jenny Diver in honor of her dexterity at plucking purses, her ingenuity and daring soon made her a legend, and her exploits earned her a place in The Newgate Calendar. Here are two:

Jenny, accompanied by one of her female accomplices, joined the crowd at the entrance of a place of worship...where a popular divine was to preach, and, observing a young gentleman with a diamond ring on his finger, she held out her hand, which he kindly received in order to assist her: at this juncture she contrived to get possession of the ring without the knowledge of the owner; after which she slipped behind her companion....Upon his leaving the meeting [the gentleman] missed his ring, and mentioned his loss to the persons who were near him, adding that he suspected it to be stolen by a woman whom he had endeavoured to assist in the crowd; but, as the thief was unknown, she escaped....

[Soon after] this exploit, Jenny procured a pair of false hands and arms to be made, and concealed her real ones under her clothes; she then, putting something beneath her stays to make herself appear as if in a state of pregnancy, repaired on a Sunday evening to the place of worship above mentioned in a sedan chair, one of the gang going before to procure a seat among the genteeler part of the congregation, and another attending in the character of a footman. Jenny being seated between two elderly ladies, each of whom had a gold watch by her side, she conducted herself with great seeming devotion; but, the service being nearly concluded, she seized the opportunity, when the ladies were standing up, of stealing their watches, which she delivered to an accomplice in an adjoining pew. The devotions being ended, the congregation were preparing to depart, when the ladies discovered their loss, and a violent clamour ensued. One of the injured parties exclaimed "That her watch must have been taken either by the devil or the pregnant woman!" on which the other said, "She could vindicate the pregnant lady, whose hands she was sure had not been removed from her lap during the whole time of her being in the pew."

At last Jenny's luck ran out, and she was captured, tried, and hung at Tyburn in 1741. Yet even at her execution, her notoriety separated her from common thieves: instead of traveling the last journey to the gallows in an open cart, she was granted a lady's farewell, and made the trip in a coach.

Above: Detail from The Rake's Progress: The Rake at the Rose Tavern by William Hogarth, 1732.

Update: I'd intended to include the link to Jenny's complete entry in The Newgate Calendar for those who are interested. My apologies for forgetting - here it is: Jenny Diver.

Monday, July 19, 2010

Ann Radcliffe

Loretta reports:

I couldn't bear to cut this one to more digestible length. She was a bestselling author who influenced Sir Walter Scott, among others, and she's still considered worth studying in English Lit classes...but, well, young women liked her books and—oh, see for yourself, and tell me what you think of this.

~~~~~

MRS. ANN RADCLIFFE.—This lady died at Pimlico, on the 10th, February, in the 54th, year of her age. She stood at the head of our Romance writers, in which species of composition she had no rival until Miss Jane Porter arose. The-popularity of Mrs. Radcliffe was at one period of her life so great, that she received considerable sums of money for the use of her name and writing prefaces; thus it stands upon many a title page, though she never wrote a line of the book; this trick of authorship benefited her purse but injured her reputation. Her principal work "The Mysteries of Udolpho," will always be read and admired.* In her description of Alpine scenery, the grandeur and sublimity of her language will never be excelled; those who have visited "Alpine Solitudes," and meditated amongst ruined castles, chateaus and monasteries, embosomed in woods nearly inaccessible from rifted rocks, and fallen torrents, with all the tremendous variety of uncultivated nature, will, in reading Mrs. Radcliffe's descriptions, imagine they have trodden the very places she delineates, it is a singular thing that she never visited the scenes she paints with the ardent imagination of an enthusiast in such gloomy colours; probably the highest hill she ever ascended, was Highgate or Shooter's Hill—the thickest wood she ever explored, Kensington Gardens, and the most amazing torrent that ever met her eye, the tide rushing through the arches of London bridge; imagination and exuberant fancy led her on to the eminence on which she rests. Her life was passed in dull uniformity, never going further than a watering place from Pimlico, where, for thirty years, she resided, her only companion being a huge pampered spaniel, for whose future support she has left £ 10. per annum.

She had an annuity settled upon her when an infant, by the earl of Charlemont (supposed to have been her father.)

She was very charitable, and never known to be out of temper. The greatest failure in her Romances, is where she attempts to describe the passion of love; but it is not to be expected that she could portray what she never felt, the only object of her affection being her dog, which is very remarkable. Mrs. Radcliffe actually believed in ghosts and apparitions, and foretold the hour of her dissolution: when the clock struck one, she doubled down the little finger of her right hand, and said to her attendant, " I shall die at four o'clock," as the hours struck she doubled her fingers, and at four o'clock, pressing down her fore finger, she said, " It is past," and turning her face on the pillow, expired without a groan. Her memory will be cherished by boarding school misses and romantic old maids, but on the shelf of literature her works will ever stand as a memorial of her talents which like her character can only be called, respectable.

~~~~~

From The Rambler's Magazine, Vol. II, 1823.

*They got that right.

I couldn't bear to cut this one to more digestible length. She was a bestselling author who influenced Sir Walter Scott, among others, and she's still considered worth studying in English Lit classes...but, well, young women liked her books and—oh, see for yourself, and tell me what you think of this.

~~~~~

MRS. ANN RADCLIFFE.—This lady died at Pimlico, on the 10th, February, in the 54th, year of her age. She stood at the head of our Romance writers, in which species of composition she had no rival until Miss Jane Porter arose. The-popularity of Mrs. Radcliffe was at one period of her life so great, that she received considerable sums of money for the use of her name and writing prefaces; thus it stands upon many a title page, though she never wrote a line of the book; this trick of authorship benefited her purse but injured her reputation. Her principal work "The Mysteries of Udolpho," will always be read and admired.* In her description of Alpine scenery, the grandeur and sublimity of her language will never be excelled; those who have visited "Alpine Solitudes," and meditated amongst ruined castles, chateaus and monasteries, embosomed in woods nearly inaccessible from rifted rocks, and fallen torrents, with all the tremendous variety of uncultivated nature, will, in reading Mrs. Radcliffe's descriptions, imagine they have trodden the very places she delineates, it is a singular thing that she never visited the scenes she paints with the ardent imagination of an enthusiast in such gloomy colours; probably the highest hill she ever ascended, was Highgate or Shooter's Hill—the thickest wood she ever explored, Kensington Gardens, and the most amazing torrent that ever met her eye, the tide rushing through the arches of London bridge; imagination and exuberant fancy led her on to the eminence on which she rests. Her life was passed in dull uniformity, never going further than a watering place from Pimlico, where, for thirty years, she resided, her only companion being a huge pampered spaniel, for whose future support she has left £ 10. per annum.

She had an annuity settled upon her when an infant, by the earl of Charlemont (supposed to have been her father.)

She was very charitable, and never known to be out of temper. The greatest failure in her Romances, is where she attempts to describe the passion of love; but it is not to be expected that she could portray what she never felt, the only object of her affection being her dog, which is very remarkable. Mrs. Radcliffe actually believed in ghosts and apparitions, and foretold the hour of her dissolution: when the clock struck one, she doubled down the little finger of her right hand, and said to her attendant, " I shall die at four o'clock," as the hours struck she doubled her fingers, and at four o'clock, pressing down her fore finger, she said, " It is past," and turning her face on the pillow, expired without a groan. Her memory will be cherished by boarding school misses and romantic old maids, but on the shelf of literature her works will ever stand as a memorial of her talents which like her character can only be called, respectable.

~~~~~

From The Rambler's Magazine, Vol. II, 1823.

*They got that right.

Sunday, July 18, 2010

Dressed for Summer: Three Eighteenth Century Women

Susan reports:

I've already shown what the 18th c. gentlemen of Colonial Williamsburg were wearing to keep relatively cool on a hot summer day, and it seems only fair to include the women today. As with their male counterparts, natural fibers are the order of the day: linen, cotton, and silk. And, also like the men, in 1775, they still consider themselves to be English to the core, and are following the same styles that their counterparts are wearing in London. Because clothing histories usually show only what the upper class ladies wore, I'm including examples from the serving/laboring class, the "middling sort"/tradesperson, and the gentry.

The young woman, top left, is dressed as a maidservant. She could also be a farmer's daughter, milk-maid, laundress, or any other woman who worked hard for her living. Because her work would likely involve physical labor, she's dressed for ease of motion as well as to keep cool. She's wearing a loose-fitting linen short gown over her linen shift and petticoat (skirt). A short gown is also an economical form of dress, with a simple construction that made a frugal use of fabric. Her apron is plain and her cap unadorned, and her only ornaments are the printed cotton cuffs on her jacket.

The next young woman, middle left, is an assistant to a mantua maker (dressmaker). She's a skilled seamstress whose daily work won't require much physical labor, and will keep her indoors. Her trade also requires her to be more aware of fashion, both as a stylish representative of her shop and her mistress and to show her own skill with a needle. She wears boned stays (corset) to give her body the conical shape fashionable in the 18th c., and her striped cotton gown is trimmed with ruffles at the cuffs and neckline. Though she's not wearing hoops, the sides and back of her polonaise are looped up to give her skirts more volume. The gown is open in the front to display her pink linen petticoat, and over that she's tied a sheer linen apron, more for style than to offer any actual protection to her petticoat. Her cap is ruffled, with a silk ribbon bow, and the single most important mark of her dress would be the thimble on her finger.

The last young woman, bottom left, is dressed as a lady, ready to pay an afternoon call on a friend. Fashion, not practicality, is her goal. Her striped polonaise is made of silk taffeta in the latest London style for 1775. The close-fitting, ruffled style, elaborately cut to display both her figure and the stripes, would have been a costly gown, using a great deal of expensive fabric. (See close-up of the bodice below left.) To give her the fashionable shape that such a gown demands, beneath it she's wearing both stays and pocket hoops. She's also the only one among these three wearing jewelry, earrings and a bead necklace. On her head she's wearing a ruffled linen cap, topped by a fine straw hat decorated with silk gauze, ribbon, and flowers (below right.) Cool for summer? Maybe. Practical? Not at all. But could there be a prettier confection for a summer day?

Photo of striped polonaise, left, courtesy of the Margaret Hunter Shop, Milliners and Mantua Makers, Colonial Williamsburg. While these ladies work in the 18th c., they do visit the 21st as well: check out their new Facebook page!

The last young woman, bottom left, is dressed as a lady, ready to pay an afternoon call on a friend. Fashion, not practicality, is her goal. Her striped polonaise is made of silk taffeta in the latest London style for 1775. The close-fitting, ruffled style, elaborately cut to display both her figure and the stripes, would have been a costly gown, using a great deal of expensive fabric. (See close-up of the bodice below left.) To give her the fashionable shape that such a gown demands, beneath it she's wearing both stays and pocket hoops. She's also the only one among these three wearing jewelry, earrings and a bead necklace. On her head she's wearing a ruffled linen cap, topped by a fine straw hat decorated with silk gauze, ribbon, and flowers (below right.) Cool for summer? Maybe. Practical? Not at all. But could there be a prettier confection for a summer day?

Photo of striped polonaise, left, courtesy of the Margaret Hunter Shop, Milliners and Mantua Makers, Colonial Williamsburg. While these ladies work in the 18th c., they do visit the 21st as well: check out their new Facebook page!

Saturday, July 17, 2010

Hot Summer Days

Susan reports:

A few more pictures from Colonial Williamsburg. Yes, it's hot, hot, hot, as it is everywhere on the East Coast this week. That pale afternoon sky tells the whole story, doesn't it?

But at least I found plenty of greenery to offer shade, as well as cheery pink phlox blossoms peeking through the white-washed fence. I'll let the string of straw hats with their streaming ribbons hint at my blog tomorrow, showing how the 18th c. ladies are keeping cool.

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Ladies' Fashions for July 1813

Loretta reports:

The ladies of 1813 are cooler, I would think, than the gentleman Susan showed us yesterday. I love the “to display perhaps rather too much of the bosom,” etc. They don’t usually editorialize—except about French fashions.

PLATE 5. — MORNING WALKING DRESS.

A CAMBRIC or jaconot muslin round robe, with long sleeves and falling collar, trimmed with a plaiting of net, or edged with lace, finished at the feet with a border of needle-work. A Cossack mantle of Pomona green-shot sarsnet, lined throughout with white silk, and bordered with a double row of Chinese binding, the ends finished with rich correspondent tassels, and a cape formed of double and deep vandyke lace. A provincial poke bonnet, of yellow quilted satin; ribband to correspond with the mantle, puffed across the crown, and tied under the chin; a small cluster of flowers placed on the left side, similar to those on the small lace cap which is seen beneath. Parasol and shoes the colour of the mantle, and gloves a pale tan colour.

PLATE 6.— EVENING OR FULL DRESS COSTUME.

A round robe of pale jonquil or canary-coloured crape, worn over a white satin slip; short sleeves composed of the shell-scallopped lace and satin, decorated with bows on the shoulders, and formed so as to display perhaps rather too much of the bosom, back, and shoulders; a broad scallopped lace finishes the robe at the feet, above which is placed a double row of plaited ribband, and a diamond clasp confines the waist in front. A Prussian helmet cap of canary-coloured sarsnet, frosted with silver, diadem and tassels to correspond; a full plume of curled ostrich feathers, inclining towards one side of the helmet; the hair divided in front of the forehead, and in loose curls on each side, with a single stray ringlet falling on the left shoulder. A cross of diamonds, suspended from a gold chain, ornaments the throat and bosom—ear-rings and bracelets to suit. Slippers of canary-coloured satin, trimmed with silver. Gloves of French kid; fan of carved ivory. An occasional scarf or shawl of white lace.

From the Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics. Authors Rudolph Ackermann, Frederic Shober. Printed, for R. Ackermann, by L. Harrison, 1813

The ladies of 1813 are cooler, I would think, than the gentleman Susan showed us yesterday. I love the “to display perhaps rather too much of the bosom,” etc. They don’t usually editorialize—except about French fashions.

PLATE 5. — MORNING WALKING DRESS.

A CAMBRIC or jaconot muslin round robe, with long sleeves and falling collar, trimmed with a plaiting of net, or edged with lace, finished at the feet with a border of needle-work. A Cossack mantle of Pomona green-shot sarsnet, lined throughout with white silk, and bordered with a double row of Chinese binding, the ends finished with rich correspondent tassels, and a cape formed of double and deep vandyke lace. A provincial poke bonnet, of yellow quilted satin; ribband to correspond with the mantle, puffed across the crown, and tied under the chin; a small cluster of flowers placed on the left side, similar to those on the small lace cap which is seen beneath. Parasol and shoes the colour of the mantle, and gloves a pale tan colour.

PLATE 6.— EVENING OR FULL DRESS COSTUME.

A round robe of pale jonquil or canary-coloured crape, worn over a white satin slip; short sleeves composed of the shell-scallopped lace and satin, decorated with bows on the shoulders, and formed so as to display perhaps rather too much of the bosom, back, and shoulders; a broad scallopped lace finishes the robe at the feet, above which is placed a double row of plaited ribband, and a diamond clasp confines the waist in front. A Prussian helmet cap of canary-coloured sarsnet, frosted with silver, diadem and tassels to correspond; a full plume of curled ostrich feathers, inclining towards one side of the helmet; the hair divided in front of the forehead, and in loose curls on each side, with a single stray ringlet falling on the left shoulder. A cross of diamonds, suspended from a gold chain, ornaments the throat and bosom—ear-rings and bracelets to suit. Slippers of canary-coloured satin, trimmed with silver. Gloves of French kid; fan of carved ivory. An occasional scarf or shawl of white lace.

From the Repository of arts, literature, commerce, manufactures, fashions and politics. Authors Rudolph Ackermann, Frederic Shober. Printed, for R. Ackermann, by L. Harrison, 1813

Keeping Cool(er) in Hot Weather, Part II

Susan reports:

I couldn't resist posting these two gentlemen that I saw this morning, strolling about Colonial Williamsburg in their summer linen. They didn't seem to be feeling the heat at all!

I couldn't resist posting these two gentlemen that I saw this morning, strolling about Colonial Williamsburg in their summer linen. They didn't seem to be feeling the heat at all!

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Keeping Cool(er) in Hot Weather

Susan reports:

Much of America is currently sweltering in July heat, and there are few places with a richer claim to swelter than Williamsburg, VA. Despite my inclination to whimper and cling pitifully to the air conditioner, I'm still venturing out to gather fresh blog-material from Colonial Williamsburg.

At this time of year, I often think of the early 17th c. English settlers who landed in the northern colonies (aka the Pilgrims), and how they were much more fortunate than those struggling to make their way in hot, humid, swampy, fever-ridden Tidewater Virginia. By the middle of the 18th c., life in the capital city of Williamsburg had progressed to a pleasingly cultured existence, but the merciless summers continued to be a fierce enemy.

Yet 18th c. Englishmen wished to remain civilized Englishmen, even in a climate bearing no resemblance to London's. How to stay stylish without keeling over from heatstroke in the middle of Duke of Gloucester Street? This gentleman that I spotted today shows how it was done. While his clothes follow the latest fashionable cut, they're made not silk or wool, but linen, the coolest and lightest of fibers. His tailor has done away with heavy linings, and his coat is about as insubstantial as it can be. His stockings are white cotton thread. He's even traded in his usual black felt hat for a white one, a dashing fancy guaranteed to turn the ladies' heads.

Much of America is currently sweltering in July heat, and there are few places with a richer claim to swelter than Williamsburg, VA. Despite my inclination to whimper and cling pitifully to the air conditioner, I'm still venturing out to gather fresh blog-material from Colonial Williamsburg.

At this time of year, I often think of the early 17th c. English settlers who landed in the northern colonies (aka the Pilgrims), and how they were much more fortunate than those struggling to make their way in hot, humid, swampy, fever-ridden Tidewater Virginia. By the middle of the 18th c., life in the capital city of Williamsburg had progressed to a pleasingly cultured existence, but the merciless summers continued to be a fierce enemy.

Yet 18th c. Englishmen wished to remain civilized Englishmen, even in a climate bearing no resemblance to London's. How to stay stylish without keeling over from heatstroke in the middle of Duke of Gloucester Street? This gentleman that I spotted today shows how it was done. While his clothes follow the latest fashionable cut, they're made not silk or wool, but linen, the coolest and lightest of fibers. His tailor has done away with heavy linings, and his coat is about as insubstantial as it can be. His stockings are white cotton thread. He's even traded in his usual black felt hat for a white one, a dashing fancy guaranteed to turn the ladies' heads.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

A man in love

Loretta reports:

I came upon this sweet little passage in The Lady’s Stratagem.* It’s taken from The Young Woman's Companion; or, Female Instructor, a book that remained in print for most of the 19th century. If the Stratagem isn’t in your budget right now, you can read more about Love & Courtship as well as receive Advice Previous to Matrimony here.

~~~~~

LOVE AND COURTSHIP,

The following are the most genuine effects of an honourable passion among men, and the most difficult to counterfeit. A young man of delicacy often betrays his passion by his too great anxiety to conceal it, especially if he have little hopes of success. True love renders a man not only respectful but timid, in his behaviour to the woman he loves. To conceal the awe which he feels, he may sometimes affect pleasantry, but it sits awkwardly on him, and he quickly relapses into seriousness. He magnifies all her real perfections in his imagination, and is either blind to her failings, or converts them into beauties.

His heart and his character will be improved in every respect by his attachment. His manners will become more gentle, and his conversation more agreeable; but diffidence and embarrassment will always make him appear to disadvantage in the company of the object of his affections.

When you observe these marks in a young man's behaviour, you must reflect seriously what you are to do. If his attachment be agreeable to you, if you feel a partiality for him, you would do well not to discover to him, at first, the full extent of your love. Your receiving his addresses shews your preference, which is all at that time he is entitled to know. If he have delicacy, he will ask for no stronger proof of your affection, for your sake; if he have sense, he will not ask it, for his own.

If you see evident proofs of a young man's attachment, and are determined to shut your heart against him; as you ever hope to be used with generosity by the person who shall engage your heart, treat him honourably and humanely. Do not suffer him to linger in a state of miserable suspense, but be anxious to let him know your sentiments concerning him.

~~~~~

*For more, see yesterday's blog

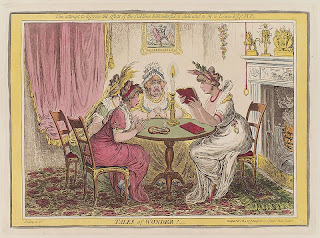

Illustrations courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Above left: A Receipt for Courtship

Below right: The Dutch Apollo!

I came upon this sweet little passage in The Lady’s Stratagem.* It’s taken from The Young Woman's Companion; or, Female Instructor, a book that remained in print for most of the 19th century. If the Stratagem isn’t in your budget right now, you can read more about Love & Courtship as well as receive Advice Previous to Matrimony here.

~~~~~

LOVE AND COURTSHIP,

The following are the most genuine effects of an honourable passion among men, and the most difficult to counterfeit. A young man of delicacy often betrays his passion by his too great anxiety to conceal it, especially if he have little hopes of success. True love renders a man not only respectful but timid, in his behaviour to the woman he loves. To conceal the awe which he feels, he may sometimes affect pleasantry, but it sits awkwardly on him, and he quickly relapses into seriousness. He magnifies all her real perfections in his imagination, and is either blind to her failings, or converts them into beauties.

His heart and his character will be improved in every respect by his attachment. His manners will become more gentle, and his conversation more agreeable; but diffidence and embarrassment will always make him appear to disadvantage in the company of the object of his affections.

When you observe these marks in a young man's behaviour, you must reflect seriously what you are to do. If his attachment be agreeable to you, if you feel a partiality for him, you would do well not to discover to him, at first, the full extent of your love. Your receiving his addresses shews your preference, which is all at that time he is entitled to know. If he have delicacy, he will ask for no stronger proof of your affection, for your sake; if he have sense, he will not ask it, for his own.

If you see evident proofs of a young man's attachment, and are determined to shut your heart against him; as you ever hope to be used with generosity by the person who shall engage your heart, treat him honourably and humanely. Do not suffer him to linger in a state of miserable suspense, but be anxious to let him know your sentiments concerning him.

~~~~~

*For more, see yesterday's blog

Illustrations courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

Above left: A Receipt for Courtship

Below right: The Dutch Apollo!

Monday, July 12, 2010

From the NHG Library: How to curtsey

Loretta reports:

My latest favorite research book is The Lady's Stratagem: A Repository of 1820s Directions for the Toilet, Mantua-Making, Stay-Making, Millinery, & Etiquette. Yes, it sounds like a tall order, but the book comes through, all 755 pages of it. Herein you will learn how ladies dyed their grey hair, what they used to clean their teeth, and what cosmetics were available. You will find instructions for making several different kinds of stays as well as how to unlace them. Want to know how to make a hat? Puzzled about the rules for mourning? Wondering how a widow ought to behave? Curious about etiquette at a dinner party? It's all here, and more, much more. The table of contents is 36 pages long.

Needless to say, I'm in love with this book. I'm not the only one. Over at the History Hoydens, Kalen Hughes provides a fine overview of the book as well as a look at the Controversy about Hair Washing.

My focus today is curtseys, which have played important roles in more than one of my books. To my delight, the book offered illustrations as well as instructions:

"The Courtesy. The following is the usual mode of performing the courtesy. First bring your front foot into the second position. (In Fig. 1, B, C, D, E, and F respectively denote the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth positions of the feet.) Then draw the other into the third behind, and pass it immediately into the fourth behind; the whole weight of your body being thrown on the front foot. Then bend your front knee, your body gently sinks, transfer your whole weight to the foot behind while rising, and gradually bring your front foot into the fourth position. Your arms should be gracefully bent, and your hands occupied in lightly holding out your gown. Your first step in walking, after the courtesy, is made with the foot which happens to be fowards at its completion. The perfect courtesy is rarely performed in society, as the general salutation is between a courtesy and a bow (see Fig. 1 G). —The Young Lady's Book."

My latest favorite research book is The Lady's Stratagem: A Repository of 1820s Directions for the Toilet, Mantua-Making, Stay-Making, Millinery, & Etiquette. Yes, it sounds like a tall order, but the book comes through, all 755 pages of it. Herein you will learn how ladies dyed their grey hair, what they used to clean their teeth, and what cosmetics were available. You will find instructions for making several different kinds of stays as well as how to unlace them. Want to know how to make a hat? Puzzled about the rules for mourning? Wondering how a widow ought to behave? Curious about etiquette at a dinner party? It's all here, and more, much more. The table of contents is 36 pages long.

Needless to say, I'm in love with this book. I'm not the only one. Over at the History Hoydens, Kalen Hughes provides a fine overview of the book as well as a look at the Controversy about Hair Washing.

My focus today is curtseys, which have played important roles in more than one of my books. To my delight, the book offered illustrations as well as instructions:

"The Courtesy. The following is the usual mode of performing the courtesy. First bring your front foot into the second position. (In Fig. 1, B, C, D, E, and F respectively denote the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth positions of the feet.) Then draw the other into the third behind, and pass it immediately into the fourth behind; the whole weight of your body being thrown on the front foot. Then bend your front knee, your body gently sinks, transfer your whole weight to the foot behind while rising, and gradually bring your front foot into the fourth position. Your arms should be gracefully bent, and your hands occupied in lightly holding out your gown. Your first step in walking, after the courtesy, is made with the foot which happens to be fowards at its completion. The perfect courtesy is rarely performed in society, as the general salutation is between a courtesy and a bow (see Fig. 1 G). —The Young Lady's Book."

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Thomas Jefferson Meets Timbaland (yes, more videos!)

Susan reports:

When I first posted a link to the Horrible Histories version of Charles II's reign, I lamented that Americans didn't seem to generate the same kind of humor about their own history.

Well, my lamentations were premature. While not quite as riotous as the HH, this video clip (from the North Carolina-based web educators Soomo Publishing) does offer an entertaining mash-up of the American Founding Fathers with One Republic's Apologize

Of course, for a better idea of how many Americans view their own history, you have to consider what Madison Avenue does to it. This recent commercial from Dodge begins well enough (the mournful fiddle, 18th c. soldiers, and romantically bleak landscape certainly caught my interest) until it takes a very strange turn with George Washington chasing redcoats a la the Dukes of Hazzard. I always forget the part of the Constitution that guarantees every American's right to an awesome ride.

But if you really want to test how culturally low you can go, here's the Bud Light commercial currently in rotation for Independence Day, with the Founding Fathers whooping it up with plenty of brew and hot historical babes. Party on, T.J.

Many thanks to Darci Tucker of American Lives for sharing the Soomo video.

Saturday, July 10, 2010

Our New Look

Susan & Loretta report:

Have you noticed we've updated our masthead?

Nothing major, mind you, just a new picture with a summertime feel. We've been asked if it's an Impressionist painting; though the picture does have that feel, it's based instead upon another of our photographs from Colonial Williamsburg. Here's the original, two ladies exchanging a bit of fresh scandal on the grass before the Governor's Palace. Our hats (or bonnets?) off to our exceptional designer, Mollie Smith, for transforming the picture into such a charming image – and also for creating our delightfully elegant "home" here at the Two Nerdy History Girls. Thank you, Mollie!

Have you noticed we've updated our masthead?

Nothing major, mind you, just a new picture with a summertime feel. We've been asked if it's an Impressionist painting; though the picture does have that feel, it's based instead upon another of our photographs from Colonial Williamsburg. Here's the original, two ladies exchanging a bit of fresh scandal on the grass before the Governor's Palace. Our hats (or bonnets?) off to our exceptional designer, Mollie Smith, for transforming the picture into such a charming image – and also for creating our delightfully elegant "home" here at the Two Nerdy History Girls. Thank you, Mollie!

Thursday, July 8, 2010

A Tureen Fit for a French Queen

Susan reports:

Every so often, I come across an object in a museum that so captures a past time and place that it stops me cold. This wonderfully baroque tureen is one of those pieces.

Made of ormolu-brass between 1720-1750, the tureen was most likely made in France. It's very large, even for a serving dish: I could probably just circle my arms around it. The tureen was commissioned by Prince Marc de Beauvau-Craon (1679-1754), below, connetable de Lorraine et vice-roi de Toscane. The son of the Marquis de Beauvau, the prince was a well-connected and powerful nobleman, and he was expected to represent both his king and France by entertaining lavishly.

To me this elaborate tureen seems to epitomize the life of the Ancien Regime at its most extravagant: exquisite craftsmanship and taste, elegant hospitality, and a reverence for fine food are all combined in a single piece. Imagine this as part of a magnificent dinner service, carried in from the kitchens by a liveried footman to guests eager to taste the delicious dish that deserved so grand a presentation.

Yet as alluring as this image may be, I have to add a few less pleasant facts about that gleaming ormolu. Also called gilt bronze in English, ormolu is everywhere in 18th c. decorative arts, from jewelry to cradling porcelain vases to the clawed feet of marble-topped bombe chests. But just like hatters and dyers, the gilders who created these masterpieces paid a deadly price for their art. Mercury was used in the process of bonding pure powdered gold to the brass or bronze base, with the result that few gilders survived their fortieth birthdays. The fatalities were so widely acknowledged that France banned the manufacture of ormolu in the 1830s, among the first legislature to protect workers from industrial hazards.

In that light, the tureen becomes an even more poignant (and more ominous) symbol of pre-Revolutionary France: artisans giving their lives for the gilded glory of aristocrats.

Above: Ormolu-brass tureen, c. 1720-1750. Gift of John T. Dorrance, Jr., Winthertur Museum.

Below: Prince Marc de Beauvau-Craon by Hyacinthe Rigaud, Nancy, Musee Lorrain

Every so often, I come across an object in a museum that so captures a past time and place that it stops me cold. This wonderfully baroque tureen is one of those pieces.

Made of ormolu-brass between 1720-1750, the tureen was most likely made in France. It's very large, even for a serving dish: I could probably just circle my arms around it. The tureen was commissioned by Prince Marc de Beauvau-Craon (1679-1754), below, connetable de Lorraine et vice-roi de Toscane. The son of the Marquis de Beauvau, the prince was a well-connected and powerful nobleman, and he was expected to represent both his king and France by entertaining lavishly.

To me this elaborate tureen seems to epitomize the life of the Ancien Regime at its most extravagant: exquisite craftsmanship and taste, elegant hospitality, and a reverence for fine food are all combined in a single piece. Imagine this as part of a magnificent dinner service, carried in from the kitchens by a liveried footman to guests eager to taste the delicious dish that deserved so grand a presentation.

Yet as alluring as this image may be, I have to add a few less pleasant facts about that gleaming ormolu. Also called gilt bronze in English, ormolu is everywhere in 18th c. decorative arts, from jewelry to cradling porcelain vases to the clawed feet of marble-topped bombe chests. But just like hatters and dyers, the gilders who created these masterpieces paid a deadly price for their art. Mercury was used in the process of bonding pure powdered gold to the brass or bronze base, with the result that few gilders survived their fortieth birthdays. The fatalities were so widely acknowledged that France banned the manufacture of ormolu in the 1830s, among the first legislature to protect workers from industrial hazards.

In that light, the tureen becomes an even more poignant (and more ominous) symbol of pre-Revolutionary France: artisans giving their lives for the gilded glory of aristocrats.

Above: Ormolu-brass tureen, c. 1720-1750. Gift of John T. Dorrance, Jr., Winthertur Museum.

Below: Prince Marc de Beauvau-Craon by Hyacinthe Rigaud, Nancy, Musee Lorrain

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

How to win the ladies in 1823

Loretta reports:

For hot weather, a little light amusement from The Rambler Magazine.

~~~~~~

Anecdotes, Bon Mots, Jeux d’Esprits, &c.

How To Win The Ladies.—The plainest man, who pays attention to women, will sometimes succeed as well as the handsomest man who does not. Wilkes observed to Lord Townsend,—

"You, my Lord, are the handsomest man in the kingdom, and I the plainest; but I would give your Lordship half an hour's start, and yet come up with you in the affections of any woman we both wished to win: because all those attentions which you would omit, on the score of your fine exterior, I should be obliged to pay, owing to the deficiencies of mine."

_____

Elopement.—The elopement of the two Miss W——'s from Staffordshire, has excited a strong sensation in that and the adjoining counties. These ladies being nearly connected with the first families in England and Wales, and the youngest only sixteen years of age. It seems, that being at Bath last winter for the completion of their education, (having lately lost their mother) they were closely beset by two young sons of Mars, and to avert the threatened danger, were sent to the house of their aunt, Mrs. A—, who is separated from her husband, and resides in the neighbourhood of Stafford.

Here, as it was more than suspected, an attempt would be made to carry them off, they were accompanied by two trusty female servants; but all the eyes of Argus were wanting ; for watching an opportunity, they got out of the drawing-room window, and ran for two miles into the turnpike road, where a coach and four, with their happy swains, awaited their arrival. Their aunt followed them as soon as she could procure four post-horses, but relinquished the pursuit at Newcastle; the lovers having got two hours a head of her in their road to Gretna Green. We understand the parties are safe returned, properly linked in the bands of wedlock.—Globe and Traveller.

From The Rambler's magazine: or, Fashionable emporium of polite literature , Volume 2. 1823

For hot weather, a little light amusement from The Rambler Magazine.

~~~~~~

Anecdotes, Bon Mots, Jeux d’Esprits, &c.

How To Win The Ladies.—The plainest man, who pays attention to women, will sometimes succeed as well as the handsomest man who does not. Wilkes observed to Lord Townsend,—

"You, my Lord, are the handsomest man in the kingdom, and I the plainest; but I would give your Lordship half an hour's start, and yet come up with you in the affections of any woman we both wished to win: because all those attentions which you would omit, on the score of your fine exterior, I should be obliged to pay, owing to the deficiencies of mine."

_____

Elopement.—The elopement of the two Miss W——'s from Staffordshire, has excited a strong sensation in that and the adjoining counties. These ladies being nearly connected with the first families in England and Wales, and the youngest only sixteen years of age. It seems, that being at Bath last winter for the completion of their education, (having lately lost their mother) they were closely beset by two young sons of Mars, and to avert the threatened danger, were sent to the house of their aunt, Mrs. A—, who is separated from her husband, and resides in the neighbourhood of Stafford.

Here, as it was more than suspected, an attempt would be made to carry them off, they were accompanied by two trusty female servants; but all the eyes of Argus were wanting ; for watching an opportunity, they got out of the drawing-room window, and ran for two miles into the turnpike road, where a coach and four, with their happy swains, awaited their arrival. Their aunt followed them as soon as she could procure four post-horses, but relinquished the pursuit at Newcastle; the lovers having got two hours a head of her in their road to Gretna Green. We understand the parties are safe returned, properly linked in the bands of wedlock.—Globe and Traveller.

From The Rambler's magazine: or, Fashionable emporium of polite literature , Volume 2. 1823

Loretta signs books in Maryland

Loretta reports:

Lucky NHG me will be signing copies of my new book, Last Night's Scandal, (yes, there will be early copies) this weekend in the company of authors Nora Roberts/J D Robb, Mary Blayney, Jocelynn Drake, Donna Kauffman, Diane Whiteside, Austin Gisriel, and Katrina Shelley.

Saturday 10 July

Turn The Page Bookstore Cafe

15th Anniversary Event

12-2 PM

18 N Main St Boonsboro MD 21713

Now I just have to figure out what to wear.

Lucky NHG me will be signing copies of my new book, Last Night's Scandal, (yes, there will be early copies) this weekend in the company of authors Nora Roberts/J D Robb, Mary Blayney, Jocelynn Drake, Donna Kauffman, Diane Whiteside, Austin Gisriel, and Katrina Shelley.

Saturday 10 July

Turn The Page Bookstore Cafe

15th Anniversary Event

12-2 PM

18 N Main St Boonsboro MD 21713

Now I just have to figure out what to wear.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

An Earlier Court Beauty Named Middleton

Susan reports:

This summer gossip 'zines on both sides of the Atlantic are feverishly hoping for the announcement of a royal wedding between Prince William of Wales and his long-time girlfriend Kate Middleton. Who doesn't love a fairy tale romance between a prince and a commoner?

But because I'm a Nerdy History Girl, especially one who's now written five novels set in the Restoration Court of Charles II, my gossip tends to come from Pepys, not People. And when I first heard of Kate Middleton, I thought instead of a much earlier Middleton lady, from a much earlier court.

Jane Needham Middleton or Myddleton (c.1646-c.1692) doesn't quite qualify as one of our Intrepid Women. She was born into Welsh gentry, and was married off at fourteen to an unimpressive gentleman ten years her senior. Her main claim to historical fame was her beauty, which was also her entree into Charles II's court. It also made her a favorite model of court painter Sir Peter Lely. Her languorous eyes and half-smile epitomized the period's beauty, and earned her a place in the collection of Lely portraits known as the Windsor Beauties (hers is left.) In the promiscuous spirit of the Restoration Court, Jane often wandered from her wifely duty with several notable gentlemen at the court, but she never found her way into the amorous king's bed – no minor accomplishment!

Like so many (too many) women of the past, Jane is defined for us almost entirely by men: by Lely's portraits, and by the famous diarists of the period. Samuel Pepys was delighted "to have the fair Mrs. Myddleton at our church, who is indeed a very beautiful lady." But she is more famously described by the waspish courtier Anthony Hamilton. Hamilton's sister, Elizabeth, had her eye on Philibert de Grammont (last seen on the TNHG gossiping here), who in turn was much more interested in Jane. Even though Jane refused Grammont's advances, Hamilton took his sister's side with a vengeance in this often-quoted bit of character assassination:

"The Middleton, handsomely made, all white and golden, had in her manners and in her way of speech something that was extremely pretentious and affected. The airs of indolent languor, which she had assumed, were not to everybody's taste; the sentiments of delicacy and refinement, which she tried to express without understanding what they meant, put her hearers to sleep; she was most tiresome when she wished to be most brilliant."

But a single off-hand comment by Jane's relative, John Evelyn, is the most tantalizing. While he, too, praises her appearance – "that famous and indeed incomparable beauty" – he also casually mentioned to Pepys that she excelled at "paynting, in which he tells me the beautiful Mrs. Middleton is most rare."

Sadly, that's all, not nearly enough for a serious historian to consider. But I write fiction, and I'm not afraid of a little conjecture. Was Evelyn's remark a condescending compliment of the "good for a girl" kind, or did Jane have real talent? Had she somehow managed to receive encouragement or instruction before she became an adolescent wife and court beauty? If she'd been born in another age, would the beauty of her paintings be remembered now instead of that of her "languorous eyes"? I wonder....

Above: Jane Needham, Mrs. Myddleton, by Sir Peter Lely, c. 1663-65, The Royal Collection

This summer gossip 'zines on both sides of the Atlantic are feverishly hoping for the announcement of a royal wedding between Prince William of Wales and his long-time girlfriend Kate Middleton. Who doesn't love a fairy tale romance between a prince and a commoner?

But because I'm a Nerdy History Girl, especially one who's now written five novels set in the Restoration Court of Charles II, my gossip tends to come from Pepys, not People. And when I first heard of Kate Middleton, I thought instead of a much earlier Middleton lady, from a much earlier court.

Jane Needham Middleton or Myddleton (c.1646-c.1692) doesn't quite qualify as one of our Intrepid Women. She was born into Welsh gentry, and was married off at fourteen to an unimpressive gentleman ten years her senior. Her main claim to historical fame was her beauty, which was also her entree into Charles II's court. It also made her a favorite model of court painter Sir Peter Lely. Her languorous eyes and half-smile epitomized the period's beauty, and earned her a place in the collection of Lely portraits known as the Windsor Beauties (hers is left.) In the promiscuous spirit of the Restoration Court, Jane often wandered from her wifely duty with several notable gentlemen at the court, but she never found her way into the amorous king's bed – no minor accomplishment!

Like so many (too many) women of the past, Jane is defined for us almost entirely by men: by Lely's portraits, and by the famous diarists of the period. Samuel Pepys was delighted "to have the fair Mrs. Myddleton at our church, who is indeed a very beautiful lady." But she is more famously described by the waspish courtier Anthony Hamilton. Hamilton's sister, Elizabeth, had her eye on Philibert de Grammont (last seen on the TNHG gossiping here), who in turn was much more interested in Jane. Even though Jane refused Grammont's advances, Hamilton took his sister's side with a vengeance in this often-quoted bit of character assassination:

"The Middleton, handsomely made, all white and golden, had in her manners and in her way of speech something that was extremely pretentious and affected. The airs of indolent languor, which she had assumed, were not to everybody's taste; the sentiments of delicacy and refinement, which she tried to express without understanding what they meant, put her hearers to sleep; she was most tiresome when she wished to be most brilliant."

But a single off-hand comment by Jane's relative, John Evelyn, is the most tantalizing. While he, too, praises her appearance – "that famous and indeed incomparable beauty" – he also casually mentioned to Pepys that she excelled at "paynting, in which he tells me the beautiful Mrs. Middleton is most rare."